On February 18, 2020, during the second round of the Semi-Finals at the televised San Antonio Rodeo, Steven and Jason Duby came tight in a near-world-record 3.5 seconds to win the round by a half-second and earn $10,000 plus advancement to the Finals, where a similar run would net them another $30,000 and a fifth-place ranking in the world.

Except they didn’t.

The brothers from Oregon were flagged out for crossfire, despite the fact that everyone in San Antone and across the country via live TV believed they watched the steer take a complete hop in tow before he was roped.

“I asked Matt Sherwood to tell them I’m sorry,” flagger Chuck Hoss said of his mistake. “I’d like to fix it, but I can’t.”

[READ: Drop it like it’s hot: The Demanding World of Today’s Flagger]

Why is it such a tough call, and how does our industry make sure the right paychecks get into the right pockets? We picked the brains of some experts for insights.

Crossfiring caught attention in the early 1970s when a couple of kids beat the pros at a big jackpot doing it. It became illegal as the late Rickey Green got very good at catching doubles in the switch. PRCA directors like Dick Yates outlawed it in the 1980s to preserve the integrity of horsemanship and roping fundamentals.

[Shop: Steven and Jason Duby’s Gear]

The Future Head Rope by Cactus Ropes

(As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.)

Back then, only a few guys could even do it. Now, not only can all the pro heelers pull it off, but scores are shorter than ever, steers are tinier and handles are faster. Worse, crossfire calls are like pass interference. Every receiver’s catch and every steer’s corner is unique. Calls aren’t open-and-shut—except the one in San Antonio.

“I knew while I was facing that it was legal, and I was about to start waving my hat,” recalled Steven Duby, 22. “I’ve never been 3 in my life!”

The shock on his face as he trailed his steer to the stripping chute was mirrored by fans and shared by PRCA Executive Council member Matt Sherwood.

“What happened in San Antonio to them was really unfair,” Sherwood said. “At a rodeo that big, we just can’t allow that.”

[Read: Egusquiza and Graves Take Top Honors in San Antonio]

Line of sight

With today’s talent, handles are blistering but subtle, so switches are slight.

“I couldn’t see that steer’s first little hit,” Hoss explained. “I was out of position a little bit. I don’t like to flag from the heeling side, but the setup was so fast, there was no way not to flag from that side.”

In world-record-fast setups, a flagger on the head side gets trapped. But a flagger on the heel side can’t see around the heel horse if he doesn’t get to a different spot within two seconds. In the PRCA, horseback flaggers can locate anywhere. In the Picket-and-Beers era, they were put at the end of the arena for a bigger view. But it was too far away.

“No matter where you sit as a flagger,” veteran NFR judge Allan Jordan said, “you better ride across there to see something. You need to fight for your position to make the best call you can make. If you get lazy, it will show in the outcome.”

To be fair, it’s not like Jason Duby hadn’t already been flagged out five times this season for crossfire. Heck, he probably crossfired their money steer back in Bracket 1 and got away with it. He lives and dies by that shot. It either disqualifies him or pays him. But that San Antonio Semi-Finals steer checked off so hard there was no way Jason could heel him in the switch.

“It made it easy not to call there, because that steer had to go forward for me to heel him,” Jason said.

Two days later, the 29-year-old from Klamath Falls threw even faster at a steer in Tucson and split the go-round.

Definition of a throw

So why is crossfire, as Sherwood puts it, “the toughest call in rodeo”? For one thing, the PRCA trains its judges to lean word-for-word on Rule R10.8.3: Any heel loop thrown before the completion of the initial switch will be considered a crossfire and no time will be recorded. But Jordan brings up a great point.

“Just because the loop caught the feet after the switch doesn’t mean it wasn’t thrown before the switch,” he said. “Is ‘thrown’ when the rope arrives or when it leaves the guy’s hand? What do you consider a ‘thrown rope’?”

Yikes. For years, judges were given this rule of thumb: A steer still swinging hasn’t switched; a steer moving forward has switched. Former judging supervisor Jack Hannum once brought the top 20 team ropers in the world to Phoenix to make a training film. Judges learned that, most of the time, when a steer is done switching, its right leg comes out to hold weight so it can go forward—and that’s typically when the heel rope can be delivered. But Jordan said those are tough subtleties for judges.

“Things happen so fast and steers check off and old steers follow the head horse … so many things go into it that even guys who’ve roped their whole life have a hard time deciding,” Sherwood said. Still, he doesn’t think semantics is the problem.

“A veteran judge knows a crossfire,” he said. “I’m not saying they’re not human and won’t get a call wrong, but how the rule is written had nothing to do with that mistake in San Antonio.”

The WCRA’s crossfire rule (11.5.1) is more detailed: The heel rope cannot touch the steer’s legs before completion of the initial switch. In the jackpotting world, former head of PRCA judges Hugh Chambliss wrote the rule for USTRC and later WSTR that always read the steer must be in tow. But there’s ambiguity in just how tight that head rope must be for “tow.” During the Equibrand USTRC ownership, it tweaked the rule to read the throw is legal as long as the header has control of the steer’s head. But yet, ambiguity. Define control in a split second? Did he have control? The USTRC flaggers said their interpretation during that period was that crossfire was legal.

[Shop: Get your arena and personal gear]

Ariat Relentless Relaxed Jeans

(As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.)

“Anyway, in 3.5 seconds, a judge has no time to go over the rulebook,” pointed out world-record-holding heeler Ryan Motes. “I think it’s simpler for judges if a steer is legal as soon as it moves forward, no matter if a guy floated his loop for three jumps or ran past.”

But what’s “forward”? Down the arena or across? Hoss says it all depends on your angle. He has proof. A crossfire (that wasn’t) cost Motes making the short round at Cheyenne Frontier Days in 2018. He and Brock Hanson had placed in the first round. In the second, Hanson over-and-undered his horse three times on a stampeding steer in soupy slop and was three-quarters of the way down the world’s longest outdoor arena when he applied epic velvet. Hanson used three hops to slow the steer down and switched him on the fourth; Motes had him on the fifth. The flagger was still loping down the center of the arena, directly behind the steer, as Hanson had been tapping the brakes. Then he wiggled the flag.

[SHOP: Brock Hanson’s Go-To Gear]

Fast Back Rope Mfg Co. Mach 3 Heel Rope

Easy Now Chute Help Shock Absorber

Roper Men’s Concealed Carry Softshell Vest

(As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.)

“Chris Horton sent that video to me and Harry Rose while we were at Dodge City,” Hoss recalled. “The heel shot looked clearly illegal. But then two minutes later, he sent us a video from a totally different angle and we could see that it was definitely not a crossfire.”

The art of not crossfiring

Most ropers know that judges aren’t out to take something away from them; they only want to protect the integrity of competition. And not a single one—not even one named Duby—wants the crossfire rule to go away.

If low-percentage crossfire shots were legal, jackpots would lose entries and fans would watch a whole lot of misses. Plus, the pros appreciate the special timing it takes to stay legal. It’s truly an art form, they say, to heel one as fast as possible after the switch.

“Nobody likes team roping without that rule,” Motes said. “Allowing crossfire teaches bad habits, bad horsemanship. You’d have a bunch of kids that can rope in the switch but can’t catch four in a row by two feet using all of the arena. And nobody can make a living throwing in the switch.”

Luckily, Steven Duby has an idea—and compassion for judges.

“A lot of us have flagged team ropings,” he said. “It’s hard. It feels like you’re out there by yourself. Especially at San Antonio, when probably four runs looked identical to our run, and you’re all alone in the decisions.”

That’s why his rule proposal requires a crossfire be called by both the line judge and the flagger—if only one of them flags the team out, the run stays legal.

“It gives the flagger a chance to say, ‘I’m not sure what happened,’” Duby said. “‘But if I’m wrong, at least it won’t cost this team winning.’”

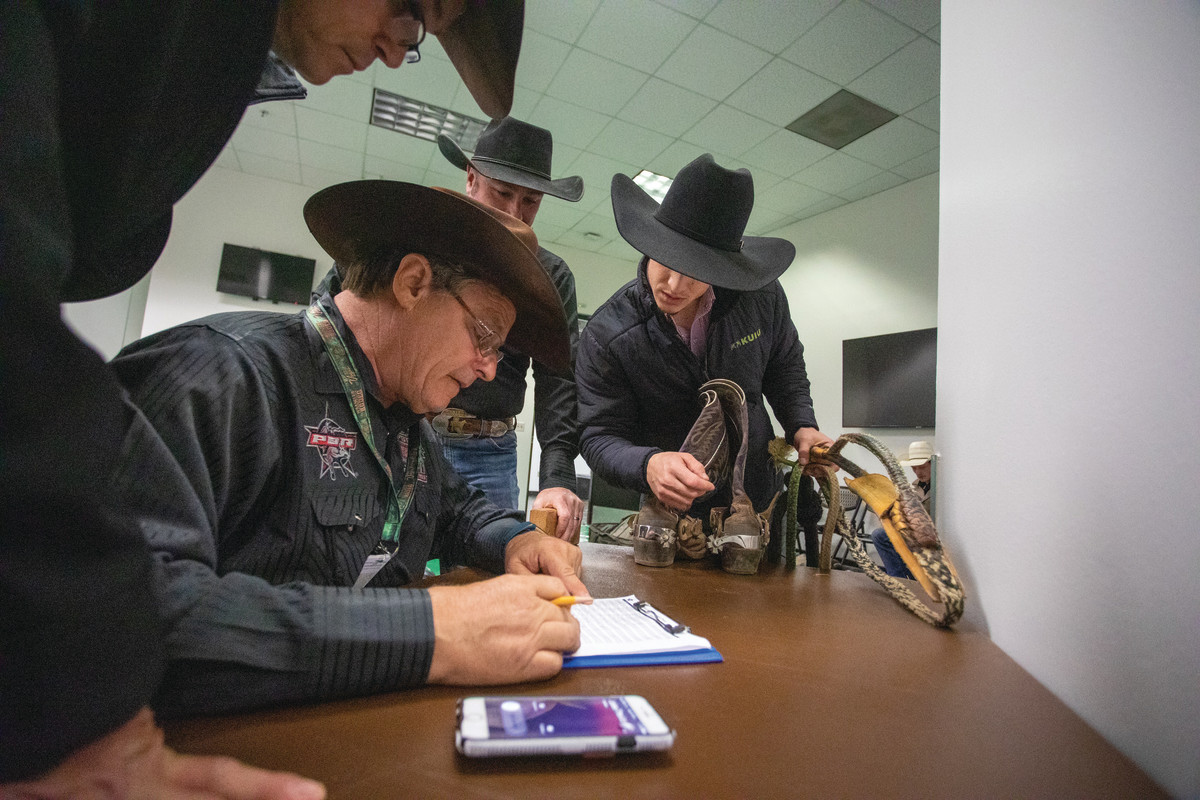

The WCRA allows multiple judges to compare from different vantage points. For a tie-down roper to be flagged out on the jerk-down rule, for example, three officials have to agree—the flagger, the line judge and another judge on the ground halfway down the arena on the right.

At the WSTR Finale, at least two judges have to agree on a crossfire, and Denny Gentry says they do occasionally reverse an initial call. But in rodeo, even if flaggers could consult the way football officials do, Sherwood isn’t sure it would work. Rodeo judges are so busy retying the barrier string and hooking the neck rope and checking the draw, they hardly have time to huddle. He prefers a rule tweak that would allow a flagger to highlight a particular run to review after the rodeo.

“If it’s a borderline call, a judge marks it and they have 30 minutes after the rodeo to flag the team out or notify them it’s legal,” Sherwood said. “If it was a crossfire, it doesn’t matter if it’s flagged out right now or later. The right call is what’s important.”

Motes goes further and suggests making crossfire a 10-second penalty instead of a no-time.

[SHOP: Gear that’s Motes-Approved]

Solid Poplin Shirt One Point Back Yoke by Roper Apparel

(As an Amazon Associate, we earn from qualifying purchases made through affiliate links.)

“If the header leaves too fast, it’s a 10-second penalty,” Motes said. “If the heeler throws too fast, it should be a 10-second penalty.”

In brackets at tournament-style rodeos that sometimes see just three or four clean times, it could advance a team that would otherwise lose a tie-breaker. At the NFR, it could make a difference in the all-important 10-head average.

“Wherever the heeler threw it, he caught the steer and that’s better than missing the steer,” Motes offered.

Rule proposals submitted to the PRCA are put on the books for a year and then voted on by the board. So none of these rules, including Duby’s proposal, would be implemented until 2022 unless marked for expedition, requiring a 7-2 vote.

“We have the greatest horses and talent in the world right now in team roping, so can we quit making the score so short?” Jordan asked. “A foot longer scoreline would relax the flagger so much. You’d have fewer missed calls, and true rodeo fans like to watch great head horses and ropers work.”

Instant replay

Regardless of tweaks to the written rule, Motes wants replay available.

“If the heel shot is borderline, flag the team out and then go look at it,” he said. “It’s the same way they call tackles in college football. Throw the flag for targeting, but then watch the replay and take it off if it’s not there.”

Jason Duby likes the idea of a PBR-like challenge button. If the call is overturned after the replay, it doesn’t cost the contestant anything. If the call stands, it could cost him a few hundred dollars that goes to the officials.

“The judges are always just doing what they feel is right,” Jason said. “At the same time, we need to be able to challenge the call sometimes. We get fined if we even speak to judges now.”

Sherwood says the PRCA hasn’t ruled out instant replay at places like the NFR or Houston or San Antonio (solely for disqualification calls). Jordan, who is also a PBR instant replay judge, likes the fact that it allows a judge to challenge and replay his own call. Replay is used in the WCRA, and association president Bobby Mote says visual evidence of mistakes offers accountability, too. Officials who miss a major call don’t need to be hired back.

But instant replay isn’t necessarily a panacea. Every arena is set up differently in roping and the cost may not be feasible.

“We did a trial run at Tucson, but you’d have to watch 10 or 12 cameras,” Jordan said.

Shoot, considering what Hoss says about angles, you’d about have to use a Go-Pro on the flagger’s cowboy hat. Plus, replay also slows down the production. Still, Mote says it only takes about one minute to view a replay at WCRA rodeos. He thinks fans appreciate it and even enjoy the controversy.

“Instant replay is the most exciting part of any football game,” Ryan Motes said. “Overtime in football is exciting and builds suspense.”

But Jordan points out something they don’t consider. What about non-calls that are challenged? Cowboys are used to “the breaks” going their way sometimes. Jordan says it caused a few fights in the PBR when it was first implemented. But WCRA’s Mote feels like fair is fair.

“Rodeos are hard enough to win as it is,” said the four-time world champion bareback rider. “I think brushing off bad calls as ‘the luck of the draw’ or ‘you win some you lose some’ is not acceptable.”

The PRCA once brought in ex-NFL officiating vice president Mike Pereira, who warns that replay was never meant for subjective calls like ball control or pass interference—or a steer’s direction change, presumably. That didn’t stop the NFL from changing the replay rule after the wrong team was likely sent to the 2018 Super Bowl, thanks to that infamous missed pass interference call.

The World Series of Team Roping uses instant replay, but only with booth review. If instant replay is ever used on rodeo’s biggest stages, like the NFR or other venues with millions of dollars at stake, organizers should keep in mind that it was meant for decisions on lines and planes—visual facts. Pereira said replaying things like whether the receiver had the ball long enough is just too subjective. Maybe analyzing the switch would be, too. As the WSTR found out, open instant replay will create challenges on the camera angle versus “my” camera angle. And some wonder where it would end. Soon we’d have to replay whether somebody got a slow flag or not.

At the end of the day, is perfection even attainable when human behavior is involved?

“A team roper came up to me at San Antonio and said, ‘You’re supposed to be a professional. How could you miss that call?’” Hoss recalled. “I told him, ‘You’re supposed to be one, too. How did you miss that steer yesterday?’”