Editor’s Note: This column was written in response to questions submitted on this topic from Spin reader Linda Barhite. Thanks for writing, Linda. Hope this helps!

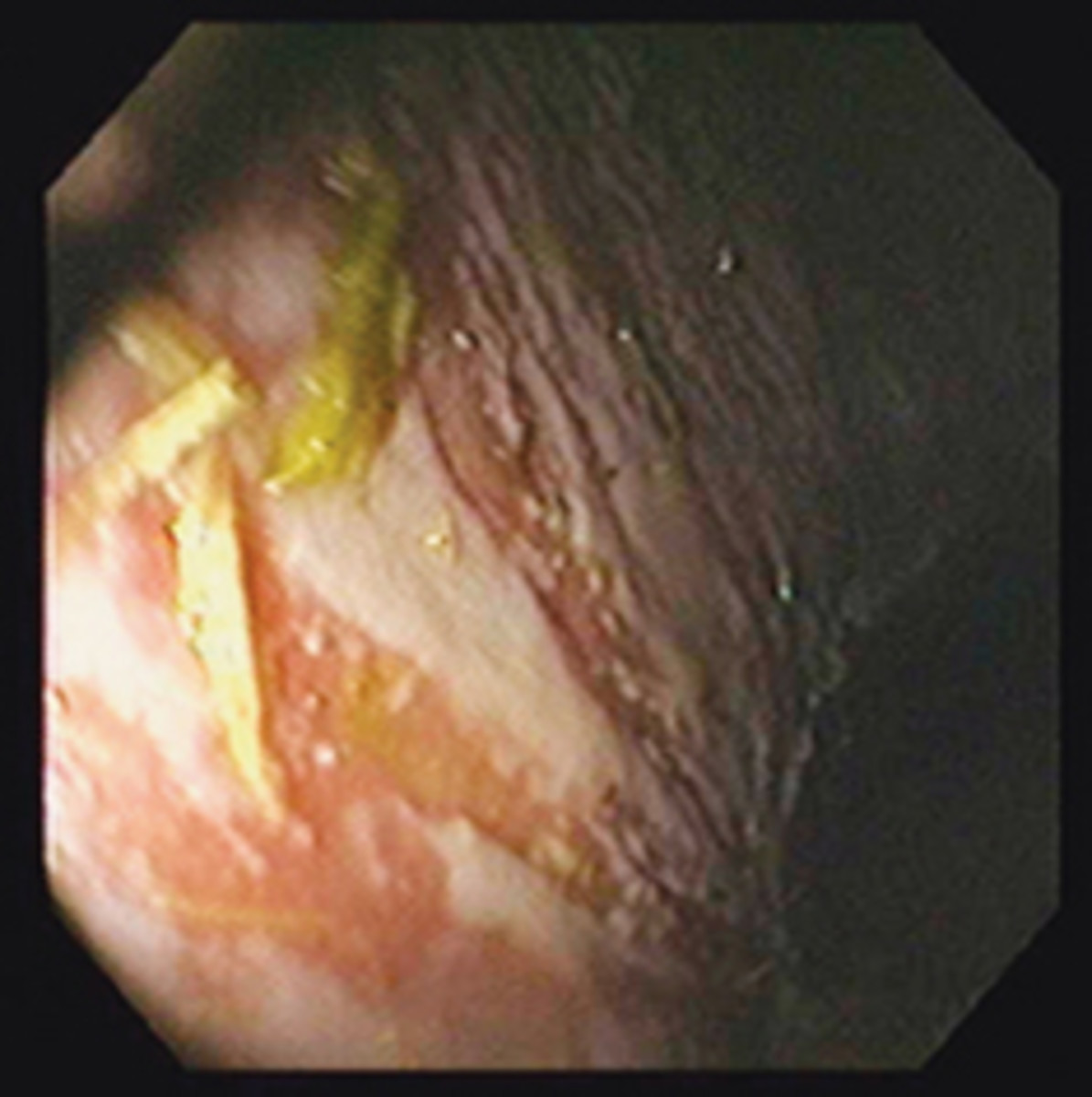

Gastric ulceration is a fairly recently recognized entity in horses. Historically, there were reports of gastric ulcers in the horse from autopsies, but it has only been in the last 30 years or so that this condition has been diagnosed clinically. The technological development of long, flexible fiber-optic scopes allowed the direct visual examination of the horse’s stomach.

After the technology became available, clinical trials were run to evaluate the incidence of this condition in the horse population. It was discovered that a significant percentage, over 50 percent, of horses in training at racetracks were affected. Some were asymptomatic and performing well, but others had symptoms of not eating well, occasional mild colic signs, or just lowered performance.

With further study, symptoms were correlated with the extent of ulcerations and the location of the ulcers in the stomach. With the knowledge and experience gained at the racetrack, it was recognized that horses in other endeavors also suffered from this affliction.

Horses at the racetrack are mostly young (typically 2-5 years old), fed diets high in carbohydrates (grain), asked to perform at intense levels, and often medicated with anti-inflammatory drugs. Stress, that great intangible, was commonly felt to be a big factor. The major conclusion from research was that abnormal amounts and distribution of stomach acid caused the ulcers.

One of the primary theories is that horses doing intense physical exercise have a higher than normal pressure in their abdominal cavity during exertion. This pressure may affect the normal distribution of stomach acid and force it up into the part of the stomach that isn’t designed to cope with the corrosive effects. It is somewhat analogous to gastric reflux disease in people.

Another etiologic factor is the NSAIDs (Non Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs), such as phenylbutazone. These drugs work by blocking products of inflammation called prostaglandins. Unfortunately, there is a type of prostaglandin that promotes the secretion of a protective mucous in the stomach. With high levels of NSAIDs, you can interfere with the natural protective mucous barrier in the stomach, making the horse more vulnerable to ulcers.

The main therapy for treating gastric ulcers in the horse is reducing the output of stomach acid. Omeprazole seems to be the drug of choice at the moment. It is branded as Prilosec in people, and Gastro-Guard in horses. A good quality diet (not too high in carbohydrates), time spent turned out and not exceeding the recommended dose of NSAIDs is also critical. Sound familiar?