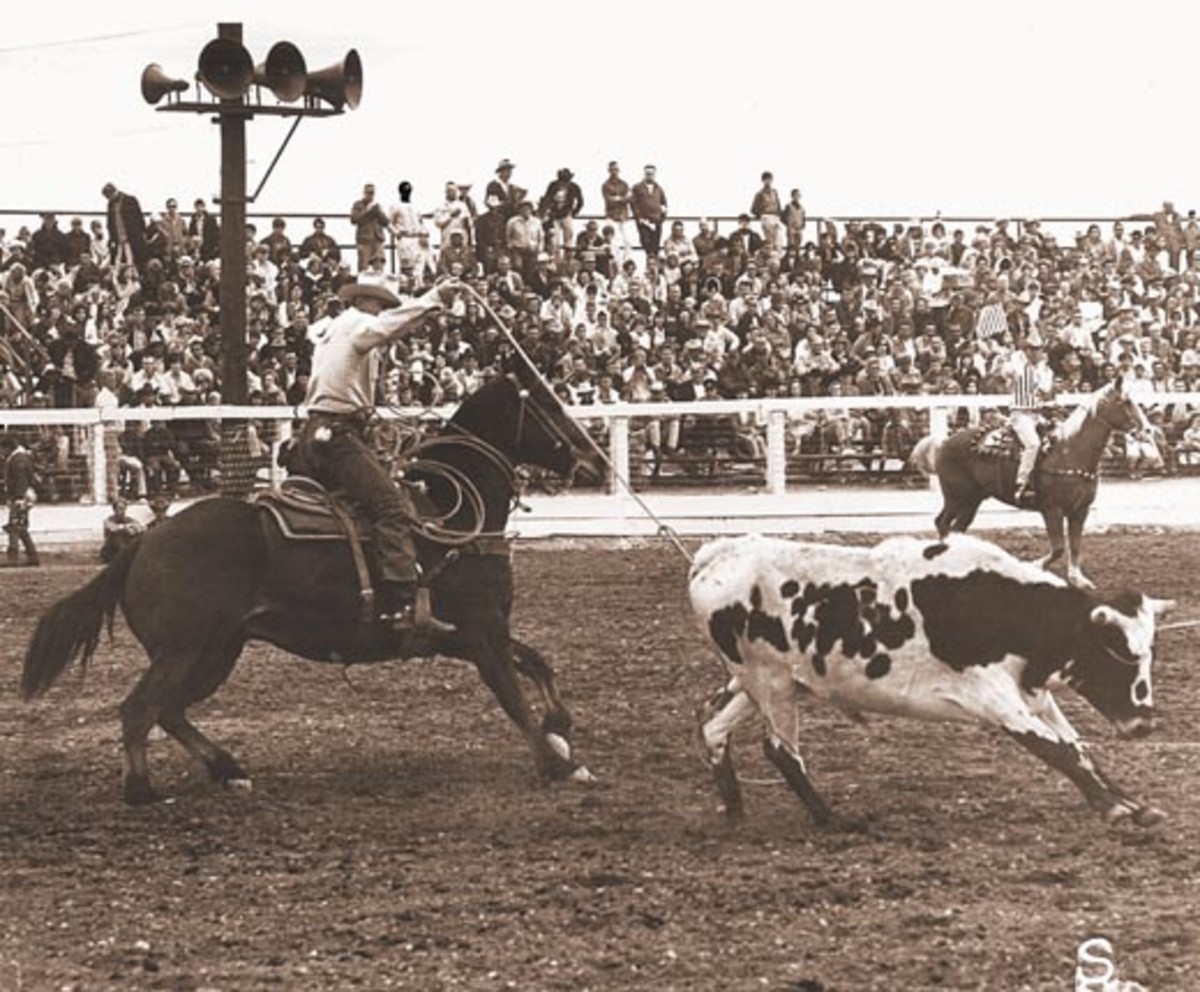

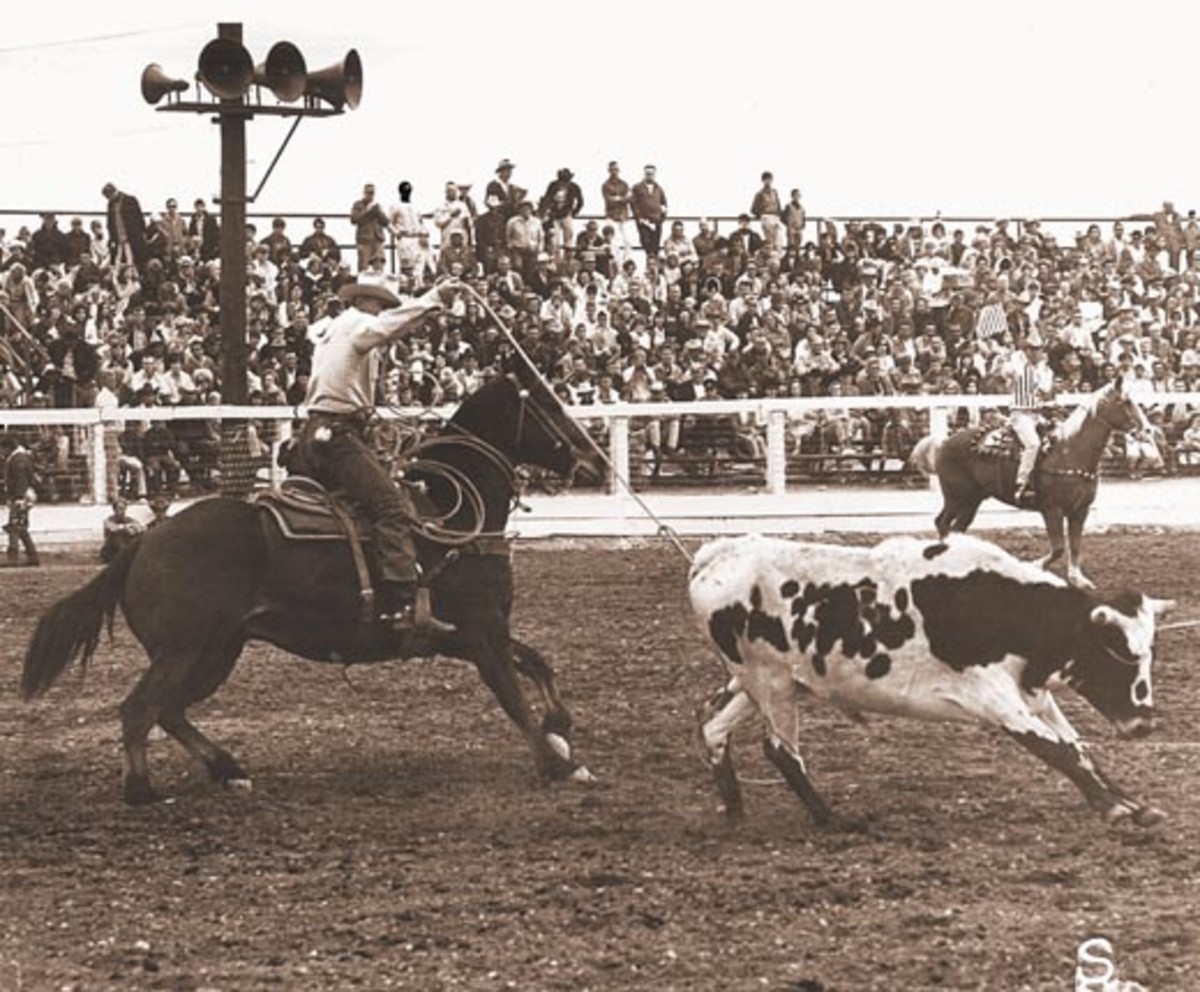

Joe Glenn rodeoed on his own terms-when it worked for him and when he could. He never did it for the fame or money (mainly because there was little of that during his era). Roping was a business for him and he loved his work. What’s more, he was an exceptional talent, perhaps due to his intense practice sessions, or maybe he was simply a natural.

Glenn was a master at both team tying and dally roping. He won his first title before there was ever an NFR and won another at the 9th annual event. As card No. 1093, he was a true pioneer in the sport, but the 1948 and 1967 world champion team roper wasn’t defined by the rodeo life. He was a husband, father and rancher first and foremost, but the man could rope. Over the years he adapted to a changing sport and in his own quiet way he influenced the way the game is played even today.

In 1914, Glenn was born in High Lonesome Canyon on the ranch his father Will-a notable steer roper in the 1920s-homesteaded outside of Douglas, Ariz., in Cochise County.

“He came from the kind of family where if they told you to jump, you asked how high once you were in the air,” his son Frank Glenn said.

In Arizona and New Mexico, team roping was better known as team tying. Competitors’ ropes were tied on hard and fast-like steer roping today. The header would rope the steer, then the heeler would rope and jerk the steer down. Next, the header would dismount, while his horse kept things tight, run down the rope and tie the back feet together with a square knot above the dewclaws.

“It was a real event,” said Billy Darnell, long-time family friend and roping partner of Glenn’s.

“It tested the horses, the ropes and the saddles. Not everybody could do the team tying. Joe was a tough competitor. If you did you’re part, he’d pay your grocery bill.”

Billy’s father, Fred, was Joe’s neighbor and the partner he won his first world title with. In fact, Fred wasn’t planning on joining the RCA but Joe needed a solid partner, so he bought his card for him. Later, Glenn encouraged Darnell to become a member of the RCA Board of Directors. His influence was quiet, but always there.

“Joe was like a second father to me,” Billy said. “My dad and Joe were friends for a long time. They worked together, laughed together, cried together and rodeoed together. Both of them had cattle ranches and both of them roped and their friendship was born out of that connection.

“He rode my dad’s horse when he won his first title, a horse called Carrot. They raised a bunch of colts out of him that were real good rope horses.”

After winning his first world title in 1948-roping with Fred Darnell-he finished fifth in 1955. Then in 1959, the first year a national finals was held, he was second to fellow ProRodeo Hall of Famer Jim Rodriguez Jr. by $64 after battling pneumonia during a cold week in Clayton, N.M.

“He rodeoed pretty hard until after he won the first one,” his son said. “For a while, he slowed down to raise his family, some years were tough with the drought and it didn’t give him the free time.”

Still, he would go to some rodeos and bring a young Frank along with him.

“I got to meet Ben Johnson,” Frank said. “He told me he really admired my dad.”

But when things got tough on the ranch, his ability with a rope came in handy. When the Southern Arizona drought was at it’s worst in the 1950s, Glenn and Darnell entered a $100 per team six-steer average roping in California. They had to rope muley Santa Gertrudis cattle in the sand.

“They drove over there and ended up paying all their groceries, feed bills and operating costs on the ranch from what they won at that one set of ropings,” Darnell said. “Joe only traveled when he could. If it was dry or the summer was tough, he’d have to stay home and take care of waters. When they could go, they prepared themselves and their horses. They believed in wet saddle blankets. They’d ride the horses hard in the morning and rope on them in the afternoons. Those horses maybe weren’t the best looking ones, but they worked really good.”

The reason they worked so well was because Joe was ahead of the curve on purposeful practice.

“He worked all his life, but rodeoing paid the grocery bill. It was a serious deal. They practiced seriously and they went at it as if they couldn’t do it at home, they couldn’t do it on the road,” Billy said. “He was always knocking at the door and they only traveled when they could; when they were practiced and ready. It was something where if they didn’t win, they had to stay home.

“Frank, Joe’s son, and I, we grew up together. We turned out a lot of cattle, put on a lot of horn wraps and exercised a lot of horses over the years. He was a professional, that guy was. We’d start practicing about two p.m. and they’d rope until dark. Generally they’d rope 60-75 head on practice days. Then they’d let us rope three or four right before dark. Looking back on those things, it was a real treat. Little did we know that Joe would go into the Hall of Fame.”

After qualifying to the first NFR ever, Glenn’s next qualification didn’t come until 1965, then he qualified to the next five-his last in 1970. He won his second title in 1967. That’s 22 years between his first world title and last NFR qualification and 19 years between championships.

Glenn, who came from the tradition of team tying, was presented with a challenge later in his career. At the Finals, ropers had to alternate between team tying and dally roping each round. With a stiff rope, older hands (he was 51 on his second of seven NFR qualifications) dallying didn’t come naturally, but he mastered it well enough to claim that second world title and several top-five finishes. While some team ropers would mount out on the nights when their particular area of expertise was not showcased, Glenn, on his top mount, Seven, could both tie-on and dally.

In those years, Glenn first roped with Art Arnold and later Billy Darnell.

“There was a long span there he didn’t even go. He was in his 50s when he and I roped,” Arnold said. “He was a pretty methodical roper. He had stuff figured out like where to have his loop pointed with whoever he was roping with so he could deliver on the next swing if everything worked-stuff nobody back then had figured out.”

He was a little unconventional, too. He used as stiff a rope as he could find.

“He used Dacron, it was so stiff you could almost sharpen the end and use it as a knife,” Arnold said. “He was the only one I knew who did.

“It wasn’t just rodeo stuff I learned from him. A lot of real life stuff just by watching and listening.”

Of course, learning from a quiet man like Glenn meant more watching than listening.

“In 1966 we won Salinas, a dally roping,” Arnold said. “At that time they had the Phoenix roping and we won that in 1967. We won two of the biggest rodeos together and one of them was dally and one of them was a team tying.”

That year, the Arnold-Glen momentum carried them to the Finals. However, since in those days they only awarded one team roping world championship, it was common practice for teams to split at the Finals to give each a chance at the title.

“When we went to the Finals I told him I probably wouldn’t go again and asked would it upset him if we split up at the Finals. He said, no, it would be fun. It changed leads about every night at the Finals, but he had it when it counted at the end.”

Without the title, Arnold competed again in 1968 to win his first title.

“I don’t know if I could have beat him that year, but his sister got sick and he had to be with her for part of the year,” Arnold said.

“Art and Joe had a rhythm,” Darnell said. “It’s like Guy Allen in the steer roping or Roy Cooper or Cody Ohl in the calf roping. It’s just a flow and they had that flow. They tied a lot of steers in 10 when they roped. If you handled one very decent at all, he’d very seldom miss. He knew what to do.”

Before Allen Bach roped with both Dennis Tryan and later his son Travis, Glenn finished his career with Billy Darnell, son of his first partner Fred. In fact, his career has other parallels to Bach’s. Bach won titles in three different decades-a feat Glenn came $64 from doing. Both men were competitive for four different decades. Bach won his latest world title at the age of 50, Darnell won his last at the age of 53. He was 56 on his last trip to the Finals.

“I remember when Joe won the world title in 1967, he roped about 95 percent of it with Art Arnold, but I roped with him a little,” Darnell said. “In the years after that I rodeoed and traveled with him. He taught me a lot about winning. He taught me that there are about four or five things you have to do to win, and you can’t cut any of them out.”

After his final qualification in 1970, Glenn retired to his Arizona ranch. In 1984, at the age of 70, he died there. Countless ropers from Southern Arizona and across the West were influenced by his style, work ethic and professionalism.

Any man’s legacy is an extension of his life, and like Glenn himself, his legacy was understated and quiet-but perhaps more relevant than people realized.

The ProRodeo Hall of Fame selection committee considered Glenn, among many others, for the class of 2007. Once his accomplishments were dusted off, Glenn became a sure thing. He wasn’t nominated and no one campaigned on his behalf. Just like in his rodeo career, he let his skills do all the talking.

“He was never the type of person for fame or accolades,” his son Frank said. “He wanted to help his partner as much as he wanted to help himself. I’m sure he wouldn’t have had a lot to say [about being inducted into the ProRodeo Hall of Fame], but it would have meant a great deal to him.”