“Splints” are a very common entity involving the splint bone in horses, usually the medial one of the front legs of the horse, that are usually only a cosmetic problem. Splint-bone fractures and injuries in horses are an entirely different entity. Splints are not so obvious or easy to identify, and have much more serious health and soundness consequences.

The splint bones run down the back or posterior edge of the cannon bone on each side of the suspensory ligament and flexor tendons. The splint bones are remnants from the time horses had five toes. At the base of the knee, the splint bones are about the size of the end of your thumb and are actually part of the lower knee joint. As they go distally they become smaller so at their distal end, about three inches above the fetlock, they’re about the size of a Q-tip.

The proximal half or two-thirds of the splint bones are attached to the cannon bone by ligamentous tissue that can be torn in young horses, causing a small amount of bleeding at the site. When this lesion heals it calcifies and forms a small bump, which is a “splint.”

Horses over the age of about 5 years rarely develop new splints, because the connection between the splint bones and cannon bone becomes a much more solid fusion.

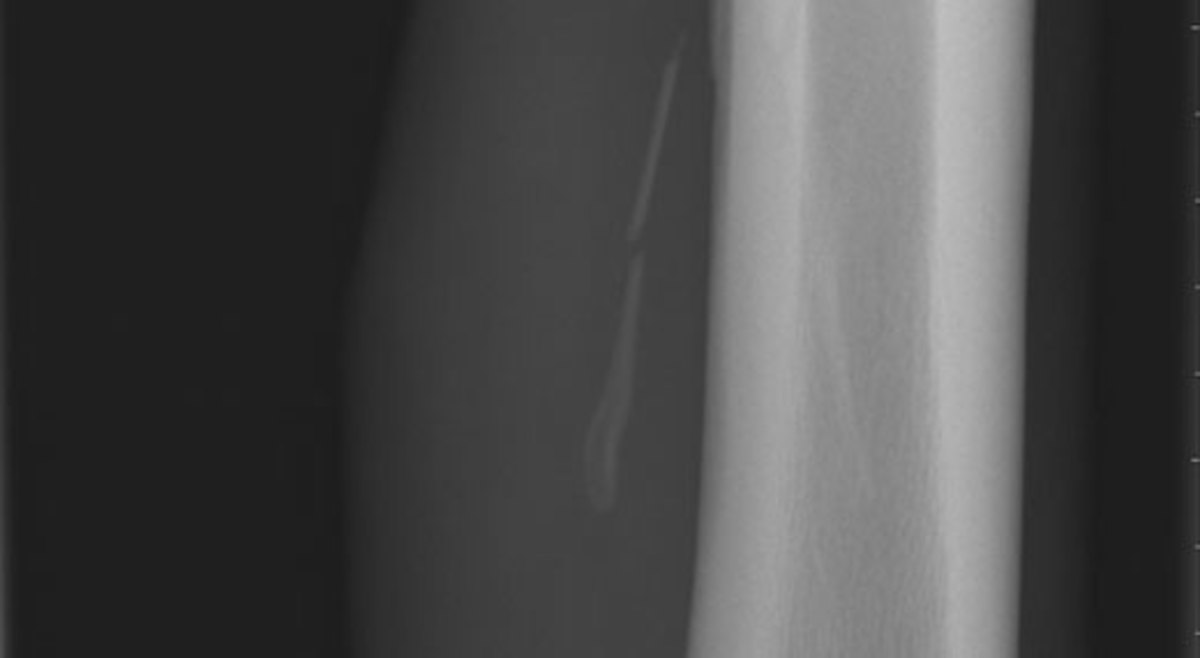

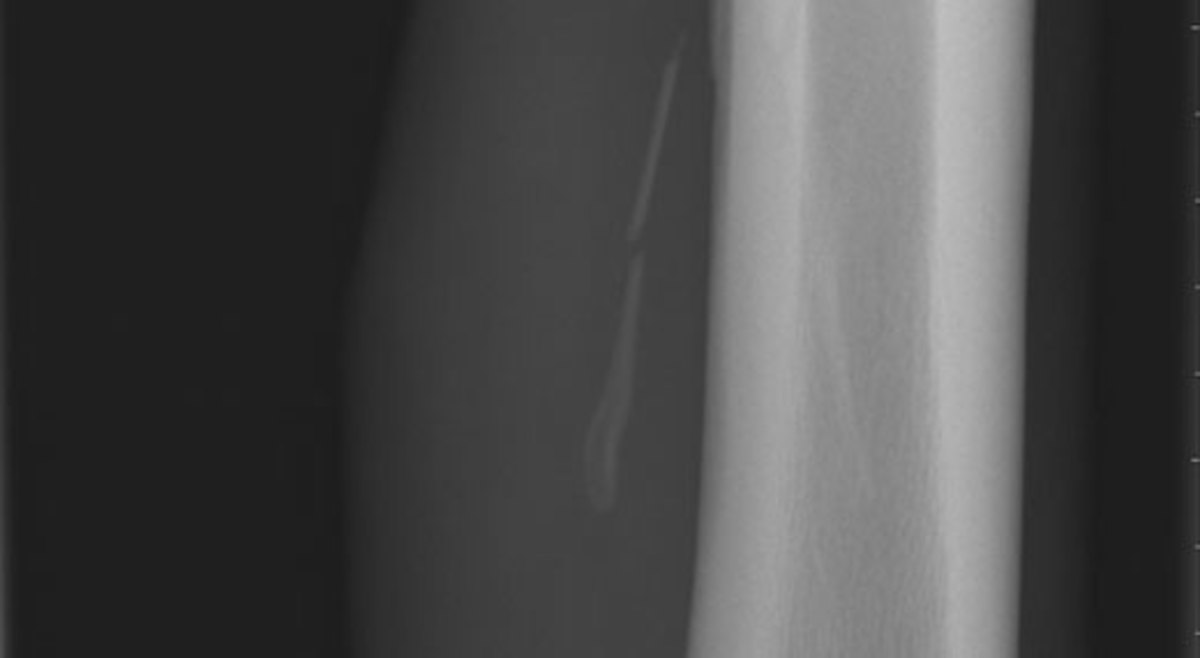

The splint bone can be fractured by direct trauma such as a horse kicking a solid object, getting kicked by another horse, or just torque from working at speed. There will usually be diffuse swelling and soreness at the time of injury, but visualizing or palpating a fractured splint is difficult. Radiographs taken at the appropriate angle are necessary to identify a fracture of the splint bone. A fracture of the distal splint bone is significant mainly because of the threat that the fractured-off segment will irritate and damage the suspensory ligament.

The suspensory ligament is a critical structure, and damage to it can seriously impact the long-term soundness of a performance horse. Because of the significance of the health of the suspensory ligament, and close-by flexor tendons, their evaluation with ultrasound scanning is indicated when a splint-bone fracture is diagnosed.

The most common method of dealing with a fracture of the distal half of a splint bone is to surgically remove the distal fragment to prevent its possibly damaging the suspensory ligament or flexor tendons. Fractures of the proximal half of a splint have to be managed in other ways, as you simply can’t just remove the proximal end of a splint bone.

The surgical removal of a distal splint-bone fragment is fairly straightforward, and only requires supportive bandaging and rest for 30 days or so to ensure healing with minimal scarring. If there has been no secondary damage to the suspensory ligament, the horse is ready to go back into training.