Everyone who enters a #15 roping in this country has National Finals Rodeo aspirations at one point or another. Some have tried to make rodeo’s Super Bowl. If they make it, it’s usually after years of paying dues. For instance, it took three-time NFR heeler Matt Zancanella eight seasons of year-round, hard-core effort before he chased an NFR steer.

That’s what makes this first NFR qualification for 8 header Elvenee Dees Jr., even more fulfilling for Zancanella. The latter will be there to watch his protégé—the kid he’s raised for 12 years—run his first NFR steer with Tyler McKnight in Dees’ third-ever season heading and second as a pro.

“I was beside myself,” said Zancanella, 41, who’d been sitting near the box last July in Salt Lake City, Utah, when Dees earned $50,000 on one steer and punched his NFR ticket. “I couldn’t believe it actually happened already. But it was the plan he’d mapped out for himself. No kid alive has watched more NFR tapes than Jr. Dees. That’s all he’s watched his whole life.”

Indeed, Dees has wanted to rope at the NFR since he was 2.

“I have every National Finals on tape from 1991 to 2016,” Dees admitted.

It’s not uncommon for the kid of a top-15 header or heeler to become an elite roper. Names like Tryan and Motes and Woodard come to mind. But it’s uncommon when they’re not kin.

Forging a bond

The story starts in the mid-1990s, when Zancanella (“Zanc”) was 18 and bought his PRCA permit. The son of veterinarian Paul Zancanella, Matt, along with his two little sisters, grew up rodeoing. The Zancanella kids left plenty of blood, sweat, and tears at the indoor arena in wintry Rock Springs, Wyoming, while their mom, Vickie, hauled them a gazillion miles to Little Britches and high school rodeos across the region.

That’s the textbook background of most any PRCA rookie—parents who poured tens of thousands of dollars into horses, diesel, and entry fees. But the story also starts with Elvenee “Ree” Dees, Sr.

Ree Dees started roping calves as a 9-year-old deep in Arizona, then turned to team roping. Announcers could never pronounce “Elvenee,” so he was given the simple nickname by his father. The family had a ranch near Yuma where they raised registered Brangus cattle.

Zancanella had seen Ree around for years when, at a roping in Indio, California, in about 2001, he lent him his heel horse.

“I placed higher on that horse and Matt told me then, ‘I want you to come on the road with us—just come to Laughlin and we’ll get you partners, a horse, and make sure you’re okay.’ And that’s what he did,” said Ree. “Matt would tell people, ‘This is the fastest black heeler alive.’”

Ree, a 7-Elite, never had the resources to rodeo for long. At the time, his son Elvenee “Jr.” Dees was about 3—roughly the same age as Zancanella’s own son, Keeton, with his ex-wife, Nancy. Out on the rodeo trail, Jr. refused to go to anybody but his dad—and Zancanella. At just 3 years old, Jr. constantly wanted to hang out with Zancanella.

“I remember at the rodeo in Guymon one year, it was real rainy and I didn’t want to go out,” said Ree. “I finally did, and here was him and Matt, out in the mud, you know?”

It’s no surprise. Kids are drawn to Zancanella because of his signature mix of realism and optimism—he’s always been as genuine as he is jovial. Zancanella is the first guy you call when your headstall just broke, or you have time to kill, or you’re trying a horse. Even if it doesn’t turn out well, you feel a lot better just having him around. According to Jr., “he tells the truth, but is positive at the same time.”

Old-fashioned tuning

In 2004, when Zancanella was about to rope at his third-straight NFR, he got a phone call. The Dees family told him Ree was going away for 10 months, and Jr. was giving his mom, Nina, too much trouble.

“He was kind of a hellion and needed somewhere to go,” said Zancanella, who welcomed the 7-year-old child with open arms. “He was always a good kid after he got lined out. It took a little bit of old-fashioned tuning, I guess.”

Jr. Dees will tell you it took quite a bit; he was “pretty bad.” Zancanella was given legal guardianship. He set a gentle but consistent premise for the kid.

“He would tell me, ‘Hey, if you’re good to me, I’m going to be good to you,’” said Dees. “In the back of my mind, I never had anything in my life, you know? So I tried to be good.”

Their home base would be Aurora, South Dakota, where Zancanella’s mom Vickie and her second husband Ken Ringdahl had settled. In the meantime, with Zancanella rodeoing full-time, his son Keeton was growing up in Wyoming with Nancy, not far from where “Grandpa Paul” and his second wife, Vicky, remain big members of the supporting cast for both boys.

Over time, Vickie Ringdahl spearheaded the same environment that nurtured Matt’s 15-year career and that of Matt’s brother-in-law, four-time NFR bulldogger Sean Mulligan—and it forged a more respectful Jr. Dees. After all, Matt and his new wife, Kristen, were giving Dees the one thing he’d most desired since he started swinging a rope. As a toddler in the park where he used to live in Yuma, Dees would catch people’s feet all day. He always had a rope in his hand.

“If all I had was a bucket with my dad, I’d rope it all day,” said Dees. “Once I moved in with Matt, he taught me to ride. He had horses and dummies and gave me the opportunity to get out of the house and do something. I never had much to do at my mom and dad’s.”

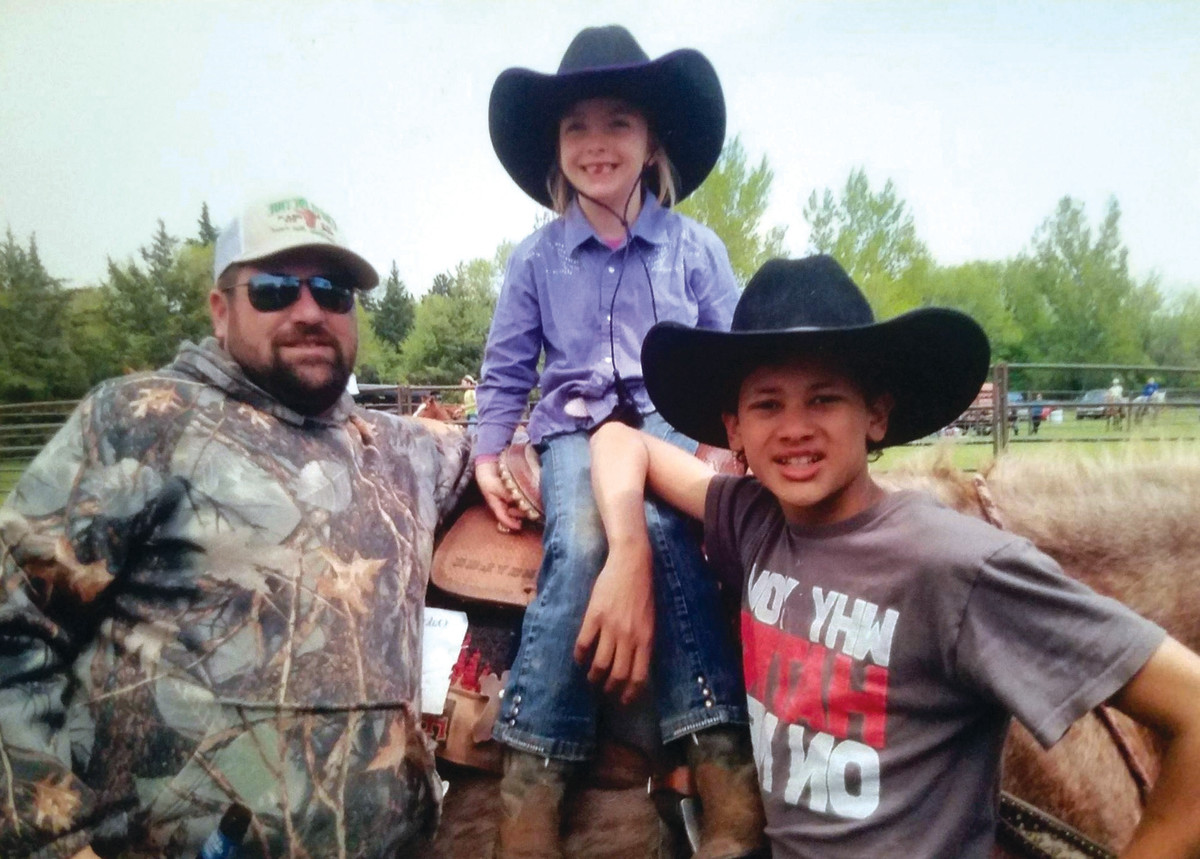

Eventually, Matt and Kristen had a daughter, Keylee, now 11, and a son, Max, who’s 6. By the time Matt and his little traveling companion began to stay home and stick to the Badlands Circuit about six years ago, Jr. Dees was brash as ever. Ropers around the Dakotas had never quite seen the likes of him. He came across cocky, but that’s been in his genes since he could walk.

“As a little boy, that kid never quit,” said Ree. “I never would let him win when we practiced, but he didn’t let nobody say they was better than him. He’s never shied away from no competition. And he never was scared, even at 3 years old.”

That’s the age Jr. was when a horse ran away with him in Yuma–an incident that would scare most toddlers into swearing off horses. But “when that horse finally stopped, Jr. was laughing,” recalled Ree. “He told everyone, ‘Next time, I’m going to jump off and bulldog!’”

Then, early into his new life with Zancanella, Jr. was clearing the arena during a Kansas City jackpot when he got bucked off so hard Zancanella thought it killed him. Jr. got right back on the horse.

Whether it’s pure fearlessness or ice coating his veins, the bravado is real. Jr. Dees doesn’t get nervous. Members of the Ringdahl, Zancanella and Dees families hold their breath when he backs in the corner for big money, but Jr. is as cool as if he were roping in a backyard somewhere.

Life-changing decisions

When Ree Dees had been released back in 2005, his parents were getting older and he felt the need to live back in Arizona with them.

“When I went back to Arizona, it was really hard,” said Ree, who now lives in Willcox. “I love my son and wanted to see him get where he is now. How could I force him to come back with me when I knew Matt was going to give him opportunities I couldn’t? We’re just thankful to Matt.

“In 2016, when Jr. and Matt came to rope at the rodeo in Buckeye (Arizona), they were 4.9,” he added. “About 20 family members were watching. I think then, they understood a little bit; they could see where Jr. was going. God has been good; He’s really been blessing us.”

Over the past decade, Jr. has known he was free to leave eastern South Dakota, but also that as long as he wanted to stay, Zancanella would be there for him. Today, Jr. remains close with his mom, his sisters, and Ree, who spent a couple of those years living in South Dakota.

“Now he’s a fixture at our house,” said Zancanella. “My dad and mom treat him like he’s theirs.”

It’s worth noting that another fixture at the house has become like a favorite uncle to Dees. About five years ago, Zancanella also took in roping-crazy Californian Mark Schmall (“Schmally”).

For Dees, growing up heeling in a house with one of the best in the world meant he won the National Little Britches World Championship at 14, and a few months later was the fastest 14-and-under heeler at the Junior World Team Roping Championships (with Junior Zambrano). Many other accolades followed. But when Dees was 17, Zancanella made him start heading.

“As a really good heeler, you’re always waiting on that good header with good horses,” said Zancanella. “But if you’re a good header, you can find a good heeler—they’re on every corner.”

Once Dees began heading, a pro partnership with his mentor was in the cards. It didn’t hurt that horses has always been Zancanella’s addiction.

“We raise barrel horses and I love head horses—I always have,” said Zancanella. “Jr. has 10 head of nice head horses.”

It’s no exaggeration. Dees knew in October that four of his horses would be good in the Thomas & Mack Center, and he couldn’t decide how many to take. Having long had an eye for and love of good horses, Matt and his family stand the barrel-racing sire Lion’s Share of Fame in Oklahoma. One of Dees’ head horses, Beemer, is a product of that program and helped him spin one in 5.8 this year at Guymon.

This month outside UNLV’s bright lights, Dees might saddle up his grulla winter-rodeo horse, Smokey, or step on his butt-dragging sorrel, Moonshine, or warm up his young green gelding, Hippy. It might be poetic justice if he saddles up the main dancing partner he’s had since he was just a kid—the grey gelding Pistol Pete—on whom he earned that fateful $52,400 in July.

Humility and heritage

That gold-medal paycheck came just eight months after Dees’ previous biggest check—another $50,000-a-man victory in the #15 Shootout at the 2016 USTRC’s Cinch National Finals of Team Roping. Dees’ mental game came together over the past year, with Zancanella’s constant guidance.

The latter would shrug when Dees came out on the losing end at jackpots, telling him losing was part of the deal. And he offered more of the same last year before they roped in Pendleton, knowing the 2016 NFR was on the line.

“Zanc said, ‘Hey, you want to make the NFR? You better cowboy up,’” Dees remembered. “And he walked by me.”

By the time Dees and McKnight nodded for that $50,000 steer on July 24, Dees was down to $19 and was ready to cowboy up. He did—becoming the first son of an African American to rope steers at the NFR in 34 years.

Jesse James, the last African American to back into the box at the Finals, had been invited to the NFR three times (1979-80 and ’83) by Allen Bach and Walt Woodard. James, now 68, helped Bach qualify for the 1979 NFR, where they won the average and Bach strapped on his first of four gold buckles.

The Californian with the outlaw name said his dad was a good cowboy. But, like Dees, James didn’t have horses as a little kid. He was raised among his mother’s Tule River Indian Tribe in the mountains northeast of Bakersfield. They had no paved roads, electricity, or running water until he was 7.

James worked on area ranches as a kid and learned to rope, noticing he could earn far more at a roping than he could working. Years of turning fast steers at 10-headers, match ropings and circuit rodeos earned him the money to buy 500 head of cattle, which he still runs on his ranch in the Sierra Nevadas.

Last fall, James was still healing from surgery to pin his pelvis back together after a head horse tripped with him in March. His son Clay, a 26-year-old former College National Finals Rodeo team roper, was working as a Hollywood cowboy–er, Indian–on the set of HBO’s Westworld.

Despite skills honed while coming of age with the likes of Camarillo, Luman and Rodriguez, James never tried to make the NFR. That’s because the economics of rodeo were no different 35 years ago – and back then, the top 15 weren’t allowed to enter ropings.

“They’d win $15,000 to $16,000 at rodeos when it would take $40,000 to $50,000 to survive,” James recalled.

December dreamin’

As for Dees, he earned $100,000 equally at one roping and one rodeo this year. He’d like to earn another $100,000 this month with McKnight, courtesy of Zancanella’s rodeo-entering savvy.

“I don’t know whether I’d have ever made the NFR in my life without Zanc,” said Dees, who’d have ranked outside the top 50 without counting Salt Lake City. “A lot of people think they’re good enough, but until you go out from January 15 until September 30, you don’t know what it takes.”

Dees was devastated in July when Matt Kasner edged Zancanella out of the Badlands Circuit heeling standings, which sent Dees to Salt Lake City without his partner. But the $50,000 winning run allowed Zancanella to go home, while Dees stayed out on the road and entered with Levi Lord.

Solo for the first time, Dees hired Keeton Zancanella (who spent last summer in South Dakota after a couple of years of college) to be his driver. The two brothers-in-arms, 19 and 20, had no fun at all hitting the road in California, just like they had at 3 and 4. They made some lightning-fast practice runs, too.

“Keeton’s getting serious about it,” said Matt. “He ropes really good.”

For December, however, Dees switched drivers to the elder Zancanella. The fact that Matt is his driver—instead of his heeler—at his first NFR makes Dees giggle. In Vegas, Zancanella is manning a booth marketing the supplement company he owns—Pro Earth Animal Health. It’s one of Dees’ sponsors, along with Willard Ropes, Best Ever Saddle Pads and Coats Saddlery.

Dees will have no shortage of number-one fans in town. His dad will be roping in the #12 at the South Point on Dec. 11. His mom will be in the Thomas & Mack, too, and was definitely one of his loudest cheerleaders at last year’s USTRC Finals. They wouldn’t mind walking across the South Point stage for the buckle presentation with their son if he should win an NFR go-round. For Zancanella, it would be a welcome return, 15 years after he split the first round in 2002 with Travis Tryan.

As for the NFR rookie himself, his strategy isn’t to win rounds.

“I might as well go win the average and place in all the rounds,” Dees said. “If I break a couple barriers, I break a couple barriers. But I’m going over there and spinning 10 of them.”

It’s classic Jr. Dees. The kid has been telling people for years what he would do and where he would do it. But to him, it’s just true.

“Everyone says they want to make the NFR,” he said. “But it’s all I’ve ever wanted. Still, I never said I’d do it until I come with Matt. It would never have happened in my life without him. Zanc is my hero.”