“Keep your head down. Work hard. Say your dreams out loud and never quit dreaming,” asserted Steve Miller.

It’s a mantra Miller has developed over the course of a life that began rooted in Montana’s logging industry. When a near-fatal accident seemingly robbed the fourth-generation logger and then-29-year-old husband and father of two of everything—he spent his first year post-accident cleaning movie theaters for a nighttime contractor—he was incapable of imagining that, in fact, an opportunity to become a leading salesman in the nation and a vice president of a beloved Western company and, above all, an artist, had just presented itself.

“I lost everything,” Miller described earnestly. “I went on food stamps. I had two little kids. I was going to bed every night saying, ‘God, help me. What am I going to do? What am I going to do?”

When a friend of his father’s offered Miller $300 a week to drive him around because he’d just had surgery, Miller found himself chauffeuring the owner of the Miracle Ear franchise, who offered to teach him how to fit hearing aids. By the end of the first week, Miller committed to a year of training to become licensed.

“I said to him, ‘I not only think I can do this, I would like to do this. You’re helping people hear again.’ You can talk about selling hearing aids all you want. I saw the people whose lives he changed.”

When it came time to take the test, only Miller and five others in the state passed. The trajectory was set. By year two, Miller was one of the top technicians in the nation, being invited to the Bahamas for company speaking engagements and to go deep-sea fishing with the company’s top brass, even though he’d never been on an airplane before.

Miller’s passion for his work and the technology continued to serve him. He became a regional manager in Southern California, then a national sales manager in Minneapolis, where he finally became VP of franchise operations. But none of it happened because it was easy.

“I did it,” he said. “Was it hard? Yes. I look back on it and I get a pit in my stomach sometimes thinking, ‘How did you do that with kids? Why would you?’ It almost scares me. But at the time, I wanted a better life and I thought I could do it.”

Growing up in Montana’s Flathead Valley, Miller always had horses and, around the same time he started his career with Miracle Ear, he pursued his longtime desire to rope.

READ: The Right Start: Finding the Right Help to Get Started in Team Roping

“So, I started roping with Jerry Hanson, who took me under his wing. And, now, Jerry Hanson says, ‘Don’t tell anybody I taught you to rope because you still suck,’” Miller revealed with great humor. “And I do. I’m just the middle of the pack, but I have a lot of fun. I’m a pay-my-entry-fees team roper, but I love it.”

As is often the case, however, as Miller’s career progressed, his time spent in the saddle waned, until he found himself sitting in his VP corner office one day hunting for companies to which he could send his resume.

“I wasn’t roping a lot, but I had a passion for roping and that was my roots.” Miller emphasized. “The Western industry and Montana was my roots. One day, I’m sitting in my seventh-floor corner office in the Dahlberg tower in Minneapolis, looking out the window and said, ‘I’m going to get in the Western industry. They must need somebody doing what I’m doing here in the Western industry. That’s all I knew. I got a Western Horseman magazine, and I sent a resume—I had a pretty good one by then—to every company I thought I might want to work for in the Western industry. And lo and behold if Dennis Portsman didn’t call me for an interview.”

READ: 33 Team Roping Journal Rules for Western Industry Work Survival

Miller joined the team at Montana Silversmiths and returned to his roots and his home state, albeit some 400 miles from his hometown—Montana’s a big state, he’ll remind you. Here, Miller’s passion for sales, the West, and finally, his art, which had been his hobby since he was a child, met.

“From my earliest memories, I was drawing on anything if I could find a pencil and getting in trouble,” Miller recounted. “I would draw in the pages of my schoolbooks and Dad would have to pay for them at the end of the year. And I got spanked—I grew up in the era where you got spankings—but I still did it.”

In grade school, Miller discovered his talents were unique when his classmates wanted his drawings and were willing to pay a nickel for them. He began painting with acrylics and, in the past few years, has discovered his love of oils. Meanwhile, his son introduced Miller to sculpting.

“Both of my brothers and my son are very artistic,” Miller noted. “As a matter of fact, my son, Jason, is a better sculptor than I will ever. I don’t know where it comes from.”

The work with Montana Silversmiths gave Miller a notable platform from which to practice his artistic talents, but his love for team roping allowed him to guide the team into new markets.

“I led the charge. Dennis wasn’t a roper. We weren’t in the trophy business. I told him, ‘Dennis, when line dancing ends, we better be in the real buckle business and that’s the award business.’ And he said, ‘We’re in the award business. We put bull riders, team ropers, whatever you want on a buckle.’

Miller wasn’t sold.

“I said, ‘That’s not the award business. That’s urban cowboy.’ So we talked and we talked to Hatco about it, and I started going to the NFR and introducing myself and meeting people and buying drinks and shaking hands and all those things you have to do and, in 1999, I got the PBR and PRCA contract for Montana Silversmiths away from Wendell Hamilton at Award Design (Medals). We were up and running in the Big Leagues, as I like to say: We are in the Big Leagues now, boy,” Miller concluded, laughing.

The work with Montana Silversmiths provided Miller with a platform and a space to create that he’d never had before. By the time Miller became Vice President, it was well-known, accepted and even encouraged that he would doodle throughout boardroom meetings.

“They would say to me, ‘Okay, let’s see what you got done today, Miller.’”

And, though untrained in the arts in general and not a buckle designer by trade, Miller designed the Bodacious buckle—the company’s first-ever, single $1-million buckle.

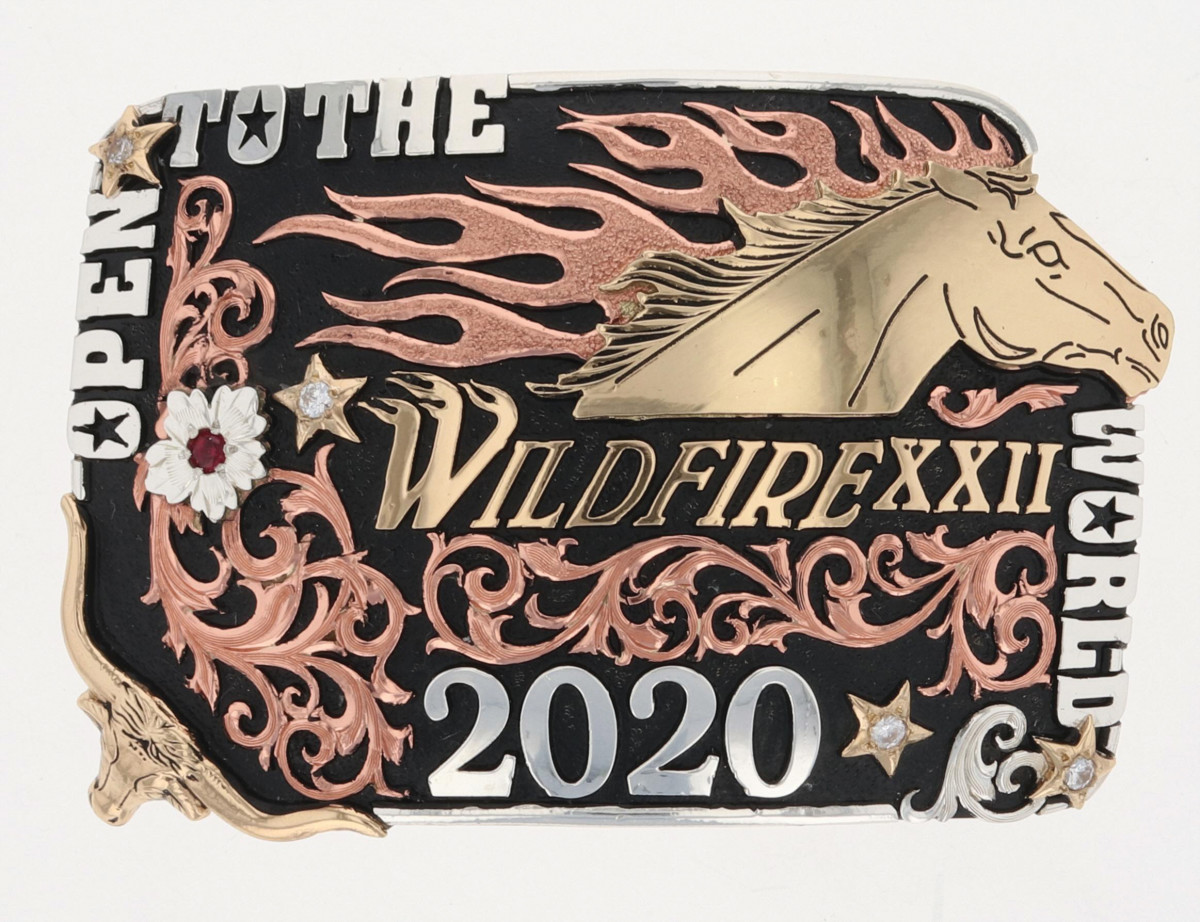

“I did the 100th buckle for the Red Bluff Rodeo. I did the special buckle for Open to the World.”

The latter came with directions to create a design that broke all the rules. Miller did just that on a bar napkin in a Montana watering hole where artistic legend (and Miller’s hero) Charlie Russel once drank while on an elk hunting trip to the Missouri breaks.

“I took the bar napkin to Billy Pipes at the NFR and said, ‘Does this break enough rules?’ He said, ‘I love it. Make it.’”

In time, it became a toss-up whether people in the industry knew Miller as a Montana Silversmith big wig or as an artist.

“I did the oil painting for the BFI two years ago, in 2020,” he recounted. “I did a commission of Karl Stressman on his horse. I did one of the president of the Reno Rodeo on his horse. I did one of a rodeo committee member in Dodge City. Joel Redmond. He had cancer and a friend of the family asked if I would paint a picture of Joel for his mother.

But the work that means the most to Miller was an opportunity realized through one of his roping partners, Dennis Limberhand, a member of the Cheyenne and living relative of the warriors who died in the Battle of Little Bighorn.

The Cheyenne refer to the event as the Battle of Greasy Grass and members of the tribe have occupied the reservation adjacent to the now National Park since the days of the battle. While white headstones adorn the hillsides marking where Custer and his men fell, only one marker exists for a single Cheyenne man who was killed and scalped when he was mistaken for a Crow.

The only person to ever be commissioned by the Cheyenne Tribal Council in association with Custer’s Battlefield, Miller created three sculptures—each depicting a historical member of the tribe who was felled in battle—for the 125th anniversary of the monument.

“It is probably the thing I am most proud of in my career and in my artwork,” Miller offered.

Talking with Miller, the joy he’s found and created throughout his life becomes abundantly clear. His own accomplishments—perhaps, more accurately, that life allowed him to succeed in the manner he did—and unforeseen turns of event wow and astonish him. He communicates all of it with contagious enthusiasm. To try to encapsulate his life in black and white on the page is, in a way, a ridiculous and futile endeavor. But, as Miller says, we should all dream big.