“This is the new normal for me,” C. Thomas Howell responded when asked if he’ll keep roping if things ever return to “normal,” post-COVID-19.

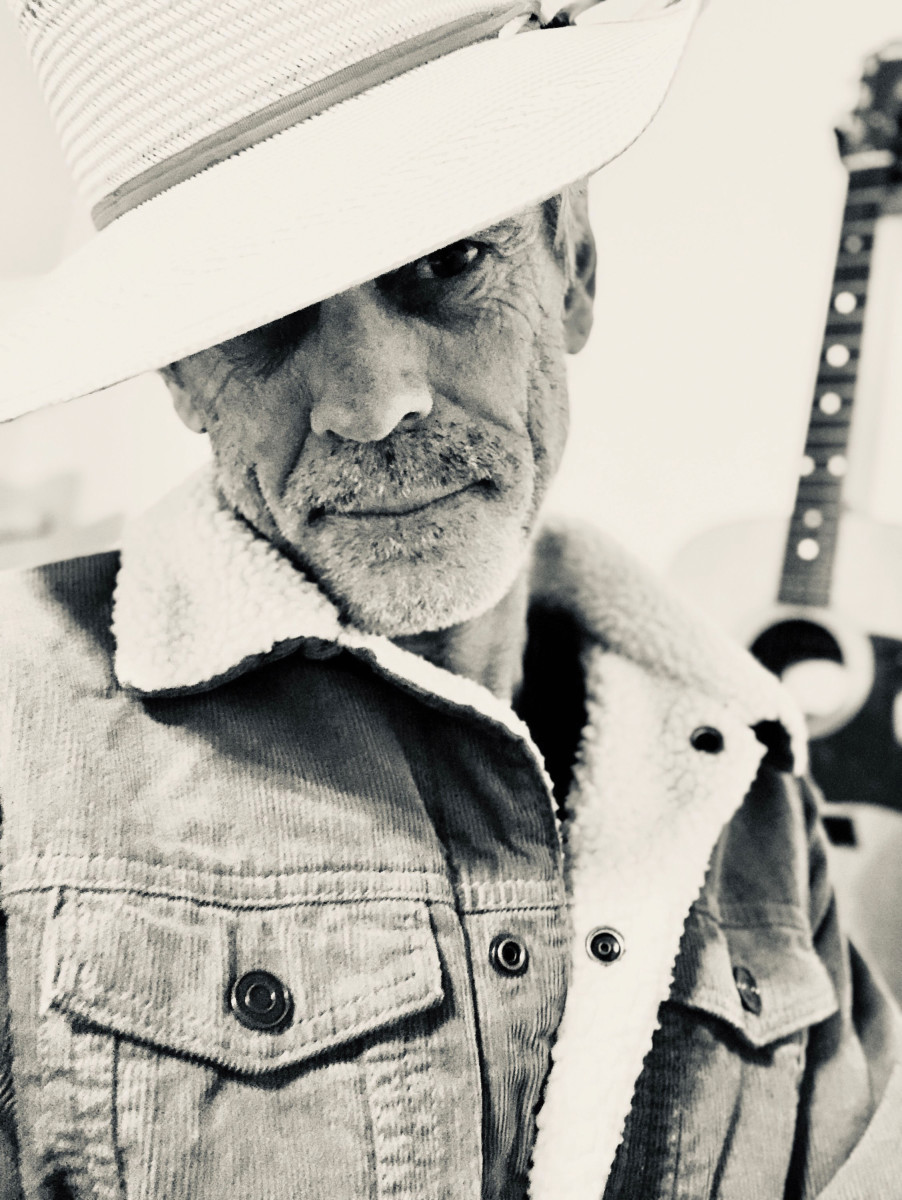

Howell, 54, is a lifelong Hollywood actor. The son of venerable stuntman Chris Howell, he grew up on set, had his first gig at age 6 and won the part of Tyler—the neighbor kid in the 1982 blockbuster, E.T.—by showing Steven Spielberg he could handle a BMX bike and a Marlboro Red. He was 12.

On one hand, he always knew that’s where he was meant to be.

“When I started working,” Howell recalled, “it wasn’t a special transition because I knew that’s what I was going to do my whole life. It wasn’t something I chased. It wasn’t something I went to college for. It wasn’t something I dreamed about. It was a very real thing. I got up early in the morning and I went to work with my dad and I was on set. I met actors and I saw directors and I was like, ‘Yea, I’m going to be here, for sure.’”

If auditioning before big-wig directors like Spielberg sounds like a lot for a barely teenaged kid, it wasn’t for Howell.

“My father was a cowboy—still is—and he was a professional bull rider for 10 years and I grew up in Junior Rodeo. In 1979, 1980 and 1981 I was California State All-Around Champion.

“I was different,” Howell continued. “People didn’t understand that I was just riding a 1,200-pound horse and roping 400-pound steers. Going into a meeting and saying hello was nothing to me. The acting was new, but I was in the spotlight by a young age. By the time I was 14, I’d won 12 saddles and I’d won probably 120 buckles. And I was going to be a pro- fessional team roper … [They’d say,] ‘That kid’s going to the NFR, no question.’”

For the record, Howell’s account of his rodeo youth isn’t painted rose with decades-spanning strokes of nostalgia, as evidenced by an interview he gave the Los Angeles Times in 1985 when he was 18.

The article quotes Howell: “I wanted to be a world champion team roper. … I still can’t admit the fact that I’ve given it up—it was my life. I still lie in bed sometimes with a knot in my stomach when anything about rodeo comes on TV. I sit there saying, ‘God, there’s Jimmy Cooper, there’s Sean—I know all these guys. But when I get around them, they say, ‘Just keep doing what you’re doing—go for it.”

And he did. E.T. led to the lead role of Ponyboy Curtis, the tender and soulful “greaser” in Francis Ford Coppola’s The Outsiders—an adaptation of S.E. Hinton’s 1967 coming-of-age novel—which basically catapulted Howell’s career into a number of successful ventures through his mid-20s. Things became challenging when the film The Young Toscanini—featuring Howell opposite Elizabeth Taylor—went sideways before its release, leaving an unfortunate mark on Howell’s own career. It took him a minute to find his way again, and a critical opportunity to play a villian in the award-winning television series Criminal Minds.

“When I hit 40, I went, ‘OK, am I going to quit this or am I going to do this?’ And I was able to reinvent myself in a role on Criminal Minds. It was a very significant role that changed my career,” Howell said of the opportunities that came to fruition following his work as the infamous criminal, The Reaper. “All the sudden, I had established this significant television career. That’s sort of where I’ve been parked for the past 15 years, is doing really good episodic television.

“My acting is better than it’s ever been. I think there’s more of an authentic self that I can find when I’m on my ranch, when I’m on my horses, when I’m roping cows, doctoring steers, building fence, whatever. This is the new normal for me. Where my place is in Rio Verde, people have roping arenas like L.A. has swimming pools. I can walk to five roping arenas. That was a pivotal decision.”

In short, keep an eye out for Howell in the future, starting with the Ariat #9.5 in Las Vegas, in which he’ll heel for his dad, whom Howell refers to as his best friend.

“It’s a little bit sad because he got me into the business,” Howell explained about his father. “And by getting me into the business as an actor, he seemingly lost his best friend and heeler because I went off on this career. It removed me from the ranch. That was sort of heartbreaking, in a way, I think, even though he couldn’t be more proud of me and what I’ve done. I know, deep down, in his heart, he lost his right-hand man and I know it cut him deep. I think [that] was a big part of why I wanted to come back now. Why he’s still roping well at 74 years old—really well, by the way. It was like, let me go give this a few years with this guy and see what we can do. I’m so grateful for that.”

While glad to be rooted in roping country again (an oportunity that was largely realized during the 2020 COVID-19 shutdown), Howell spent a number of years living in big cities across the globe—a lifestyle that supported his roping ambitions not at all. It was a clean 25-year break, so the return to the arena has been something of a time warp for him.

“When I used to rope back in the ’80s, it was a very different style. As a header, you didn’t really roll ’em down the arena like you do now. You used to just stick ’em and move ’em. All the good ropers that I roped with, they didn’t want a handle. They would just say, ‘Go left. Move them.’”

Rodeo travel looked a lot different, too.

“We didn’t have goosenecks and living quarters. We didn’t have phones. At 2 o’clock in the morning, you didn’t dial up a mare motel on your phone, plug in and go to sleep in your bed! You were banging on people’s houses going, ‘Can we keep our horses here?,’ and they’re answering doors with shotguns and you’re going, ‘Man, we’re not from here, we just want to put our horses in your barn. Don’t shoot us!’ That was just normal and now it’s so different. It’s just a different world.”

What’s not terribly different, however, is the community. In the arena, Howell is just a roper again: “It’s equal grounds there. Hollywood doesn’t have a voice in the roping arena,” he said.

“To me, it’s a place to go and really rejuvenate and let go; do something that I love; be with people that are really good people that don’t care what you do. I just want to watch good ropers and good runs and talk to them about things and see people that I’ve known for a long time and see the kids that I used to know when they were little bitty kids growing up, roping great and let them know about stories about their daddy … things like that. That, to me, is what really matters. That’s what the arena offers.”