Kycen Winn of Annabella, Utah, comes from a tight family who all saddled up to rope every single evening as the sun sank into the dust, just like the Corkills did in Fallon or the Brays in Stephenville. It’s their life.

Kycen’s dad Brian Winn, 54, is a 7 header who terrorized the Wilderness Circuit for the past 30 years. His older and younger sons rope, too, but Kycen, now 28, was eaten up with it. He studied heeling, hard. As a kid, he loved to come along to the big slacks.

“As soon as he got out of the truck, he was always looking for the best heeler there,” said Brian. “He’d follow him around all day asking how he did things. Even if it was the No. 1 guy in the world, he’d ask all his questions.”

Kycen became an 8.5 as a teenager. After five qualifications to the College National Finals Rodeo (thanks to the pandemic)—where he won three total go-rounds—plus a 2018 trip to Vegas where he won the $234,000 YETI 13 Finale—he was bumped to a 9.5. He was a 10 heeler by the time he was 22.

The following summer, right before he was headed to the 2019 BFI in Reno, a horse fell with him and it dislocated his right shoulder. Luckily, his mom’s a nurse. She popped it back into place. Winn roped at the Feist and later made the Wilderness Circuit Finals. But the injury would nag him continually.

“I was at a roping once in St. George,” recalled Winn. “Me and Hagen Peterson were high call. He turned the steer and I heeled him and pulled my slack, and my shoulder just fell out of the socket. I could barely dally. It had come out so often, by then, that it just started falling out.”

Winn’s goal was to become a world champ, but his dad had warned him to have everything in place first. So, he’d spent years saving every dollar from riding rope horses for Jason Hershberger or Cole Clements and jackpotting. Finally, he’d amassed five good horses, a big chunk of money and lined up a two-time world champ—fellow Utah native Matt Sherwood—to spin for him.

“I was finally ready to pull the trigger and leave and go do it,” Winn said. “That’s when they talked me into getting that shoulder fixed.”

Unfortunate snip

He went under the knife in the fall of 2022 and thought he’d be back to hocking steers by March. But after the operation, it was clear something was very wrong.

“If my arm was hanging at my side, I could only move it 3 or 4 inches, even 2 months later,” Winn said. “I was freaking out. Finally, they told me the main goal was just to get to where I could use the arm, and not worry about ever roping again.”

Reeling from that news, and a second surgery on the “frozen shoulder” that made it even worse, Winn sought out other opinions. He discovered the original surgeon had actually damaged his brachial plexus—the network of nerves that sends signals from the spinal cord to the shoulder, arm, and hand.

“I couldn’t believe it,” he said. “For 11 months, I struggled really bad with mental health.”

The budding superstar didn’t touch a rope or watch a rodeo until the following year. He sold every horse he owned, for cheap. He got to where he hated horses.

“My parents came and got my saddles and I had hundreds of bits; they came and locked it all up because I was selling everything,” he said.

Fellow Utah native and three-time NFR roper Quinn Kesler was one of those checking on and encouraging Kycen. They’d grown up in each other’s arenas and the families were very close. Kesler’s suicide in February 2024 contained, tragically, a timely message for Winn.

“When I saw everybody go through the aftermath of Quinn’s death,” he said. “I kind of knew I needed to get some help, so got some counseling.”

Liking it again

Mostly, though, Winn relied on his family, who never gave up using his heritage to heal his mind.

Late last spring, he finally saddled one of his dad’s horses and grabbed an old head rope to try and get his old fix. But he hit his horse in the head with every swing. Devastated, he tried heeling left-handed. At first, he never hit one. Kycen practiced until he could catch two feet, but dallying left-handed was always a fiasco. When Global Handicaps wouldn’t let him tie on—or rope left-handed as less than a 6.5—he gave up again, for months.

His father, who still gets emotional talking about it, said he never worried about the risk of encouraging his son to keep trying something so clearly impossible.

“Kycen was already struggling mentally, anyway,” said Brian, an assistant school principal who never says die. “I thought roping was only going to help. I would never tell him to give up. He just loves it too much, you know? He’s a whole different person when he gets to rope. Anybody who grew up doing it just knows—nothing replaces that feeling.”

In the meantime, after months of using mostly his left arm to golf, plus hundreds of sessions of physical therapy, Kycen could lift his right arm about 45 degrees. He started messing around, swinging a rope out to the side. He found that by leaning his body out, he could just barely get his swing to clear his horse’s head. Every day, Brian would turn a trotter several times for Kycen. For weeks at a time, he didn’t catch any feet at all.

“The first time I caught that steer right-handed and dallied at my dad’s house, I pulled back like I just won the Finale again,” he said.

Steady improvement

Winn now has 30 percent use of his right arm. The heeler who reached roping’s highest level by swinging with his tip way down over the left side of his horse? Now his only power is in his wrist.

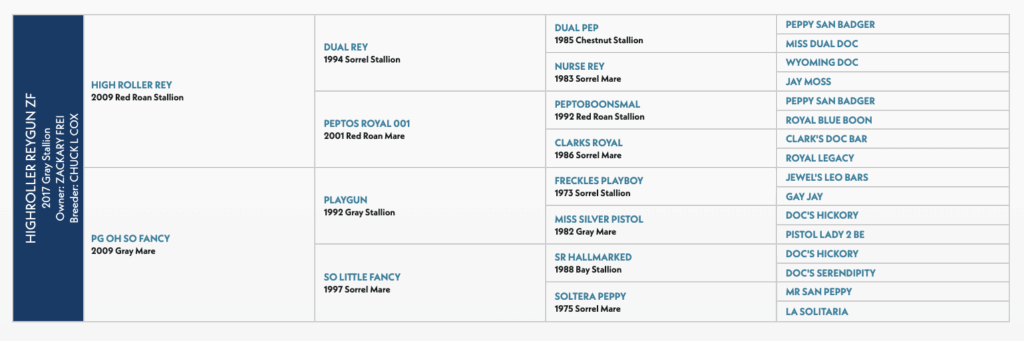

He rides down the arena swinging a super-fast, almost underhanded, branding-pen loop with which no one’s ever hit the pay window in a high-numbered roping. But with the help of 8-year-old High Roller Reygun ZF—the super-honest Dual Rey/Playgun stallion he’d started as a colt—Winn is doing it. Of course, it’s not all rainbows and butterflies as he found out in Reno last fall at the ACTRA Finals.

“That was a long week,” said Brian. “Of course, he still wants to enter everything. He dislocated and almost cut his thumb off one day and his shoulder went out of the socket the next day. He was at the hospital every day.”

Kycen simply found a local doctor to reposition his thumb, which was turned around pointing at him, and braced it so he could rope the rest of the week (he won the Century roping with Steve Dugger). From there, he wintered in Arizona because the Utah cold hurts his arm so much. In February, he placed with his dad in the #13 Pre-Roping during the Mike Cervi Jr. Memorial.

“At the Cervi, I hadn’t seen any of those guys for 3 or 4 years and they were all checking on me, and still shoot me a text to see how I’m doing,” said Winn. “I just think the rodeo community is so amazing.”

Wesley Thorp, who knew Kycen was on track to earn a gold buckle like one of his own three, marvels at the physical pain the kid endures just to rope.

“It hurts him so bad just to grab his slack, and his right hand doesn’t work the same, so dallying is a challenge,” said Thorp. “He kept such a good attitude, supporting his buddies the whole time. And knowing he can’t use his arm, it just shows you how good that guy’s timing really is, and his riding and his feel for the tip of his rope.”

In March, just before he headed north, Winn was on a heel horse that fell with him, breaking his ribs and a bone in that same right shoulder. But he healed up in time to win an amateur rodeo with his little brother Ryder, 17, in Spanish Fork. Now, Kycen’s goal is to win the RMPRA’s year-end championship that eluded him as a youngster.

In fact, Sherwood sees that 6.5 as rejuvenating for Kycen, at this point. Ironically, the numbering system as we know it (the USTRC) was launched 35 years ago by a man who designed it for this.

Physical limitations

“It’s really why we have handicaps,” said Denny Gentry, who, as a young man was aboard a water ski when a head-on impact with a railroad bridge blew both his elbows out and required steel rods in both arms. Like Winn, Gentry’s post-injury swing was low and affected his follow-through. Where Winn has to lean back for enough extension, Gentry had to get very close to a steer and then lean forward—which made his horses very short.

“I finally had to learn how to heel,” Gentry said. “After my wreck, I remember I didn’t want to quit roping, but still wanted to be able to compete. At the time, my thought was that people are all handicapped in one form or another—or will be at some point.”

Until 2017, a medical appeal for a lower number had an expiration date and reverted back. But today, classification analysis is 100 percent computerized. Global Handicaps’s latest software can finally adjust ropers down if necessary—not just up. For now, Winn’s 6.5 is giving him a chance to do what he built his entire life around. In December, he’ll take his dad back to Vegas to enter the #13.5 Finale for the first time since he won it 7 years ago.

“Without my dad, I’d have quit,” said Kycen. “From the time I was little, I loved going out there and heeling for him. I just knew he could help me and we’d figure it out. He’s super patient. I would get so mad and tell him, ‘I’m done; I don’t even want to be around it,’ and then he’d call and say, ‘Come on, we’re headed to Pleasant Grove,’ so I’d jump in and go. He took me, almost like I was a kid again, you know, and got me re-hooked on it.”

Brian said the family’s Mormon faith helps them look for reasons to be grateful. He’s pleased that when Kycen’s dream of roping for a living was sliced along with his brachial plexus, he became an entrepreneur. Kycen and his wife, Kamryn, own Double K Custom, which builds pipe fences and steel buildings, plus a fabrication shop with six to eight employees. Kamryn, a tough header who always pushed her husband to keep trying to rope, does the books for the businesses, gave birth to their baby girl last winter, and manages their stallion bookings.

Roping handicapped

Despite Winn’s unbelievable return to the arena, he can only pull his slack so high, and loses legs. His delivery is tricky coming from the side instead of being able to come down with his arm. He can only throw from one position, so the handle is crucial—he’ll miss 8 out of 10 that drift down the arena.

“Timing is so hard now,” he said. “Generally, if you’re out of time with a steer, you need to speed your swing up. I can’t do that. I actually have to slow it down by taking one big swing. I can’t be fundamentally correct anymore, even though when I get to the corner, I can still see it so good. That’s the most frustrating thing.”

Sherwood, who roped at the BFI twice with Kycen, said the kid’s impeccable pre-injury timing helped him relearn to rope with a different swing. And, oh, the perseverance.

“Every time an athlete is injured, his only question is ‘How long until I can play again?’” said Sherwood. “Kycen had that mentality for a while. Then, he thought he’d never play again. But you can have those thoughts without it making you a quitter. It’s like, ‘I know how good I can rope—I’ll figure this out with my elbow down.’”

Today, Winn remains immensely grateful to his wife and family, but also to the only sponsors that didn’t ditch him during this journey: Classic Ropes, Classic Equine, Coats Saddles, Key-Lix equine supplements and Best Ever pads.

It already took talent, passion and extreme dedication to reach the highest level of his sport. What then, did it take for Winn to start completely over despite so much physical pain and mental frustration? Pure obsession. Kycen Winn loves heeling as much as he ever did. He’d do it again all day, every day, if he could.

“Team roping is probably one of the most addicting things, ever,” Winn admitted. “Because of the daily challenge of knowing it’s something that can never be perfected.”

—TRJ—