There are numerous destinations throughout the American West to encounter one of Chris Navarro’s many monumental bronze sculptures, but “Champion Lane Frost” on the grounds at Cheyenne’s Frontier Park in Wyoming, “The Messenger” at The Alamo in San Antonio, and “When Champions Meet” at the Greeley Stampede’s Island Grove Regional Park in Colorado are just a few you may have met in your rodeo travels.

And, if you’re prone to visiting galleries or Western art shows and museums, the chance of witnessing a Navarro work in living color increases exponentially. His work proliferates the masterfully lit walls and pedestals of places like the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Musuem in Oklahoma City, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, and the Pro Rodeo Hall of Fame in Colorado Springs, Colorado. This March, he was a featured artist in the acclaimed Night of Artists show at San Antonio’s Briscoe Western Art Museum and, in 2015, he was the Honorary Artist for the Buffalo Bill Art Show in Cody.

Navarro, 65, who spent his younger years aboard bulls and bareback broncs in the rodeo arena, lacks any kind of formal training in the arts—a detail that has, arguably, aided him in his successes.

“I’m self-educated. I don’t like to tell people I’m self-taught. There’s a famous saying by Ben Franklin. He says, ‘You show me someone who’s self-taught, I’ll show you someone who had a fool for a teacher.’

“You learn from everybody. It’s not like some lightning bolt hits you and you’re endowed. Just like rodeo. I didn’t have any history in rodeo. My dad was a 30-year military officer. I got my first horse when I was 12 and then I started showing in 4-H, and then we got transferred overseas and there was a military rodeo circuit and I saw these guys riding bulls and broncs one day and I thought, ‘Man, that looks like a lot of fun.’ I was 16. That’s how I got started in rodeo.”

Navarro moved to Wyoming to rodeo at Casper College but, by 23, had come to the realization that he wasn’t going to make a living rodeoing. On a hunting trip and a tour of the property owner’s home by the caretaker, Navarro came face to face with a 40-inch bronze, sculpted by the homeowner.

“I quit riding roughtstock and I thought something was missing in my life. I saw this beautiful bronze by a sculptor named Harry Jackson. It’s called ‘Two Champs.’”

Feeling a connection to the work, Navarro inquired about its cost and, when he was told $35,000, he determined he’d make his own.

“I went to the art store and bought my supplies and started sculpting. I went to the library and got every book I could on it. Went back to the little trailer house I was living in and made my first sculpture, called ‘Spinning and Winning.’”

The piece, which captures a moment during a mighty bull ride, caught the attention of the man at the foundry, who convinced Navarro to let him enter the work in an amateur division at a local art show.

“I won a blue ribbon and $15. I knew I was onto something,” Navarro said, chuckling a bit at his modest start.

Now, 40-some years later, what Navarro really knows is that it pays to try.

“I’ve never let my lack of experience keep me from trying to do something, really. That’s one of the strong suits of it: having that kind of attitude and belief. Plus, one thing rodeo teaches you is you need grit. You need grit in this art world business, too. You need grit in everything, really.”

That goes for the roping arena, too, which Navarro didn’t enter until he was 39, but readily admits to feeding his addiction to it each winter when he travels from his home town of Casper, Wyoming, to Sedona, Arizona, where he owns the Navarro Gallery and Sculpture Garden.

“I travel 500 miles a week to go rope down in the valley,” said the 4.5 header. “It’s all I want to do. I love team roping. It’s like an addiction. You just want to keep doing it.”

For Navarro, team roping provides a lot of the reward that rodeoing did in his youth, without so much of the risk.

“I think a lot of guys who used to ride roughstock like to rope because you don’t have to worry about getting cratered all the time, but you still get that little adrenaline rush. At least that’s what it is for me.”

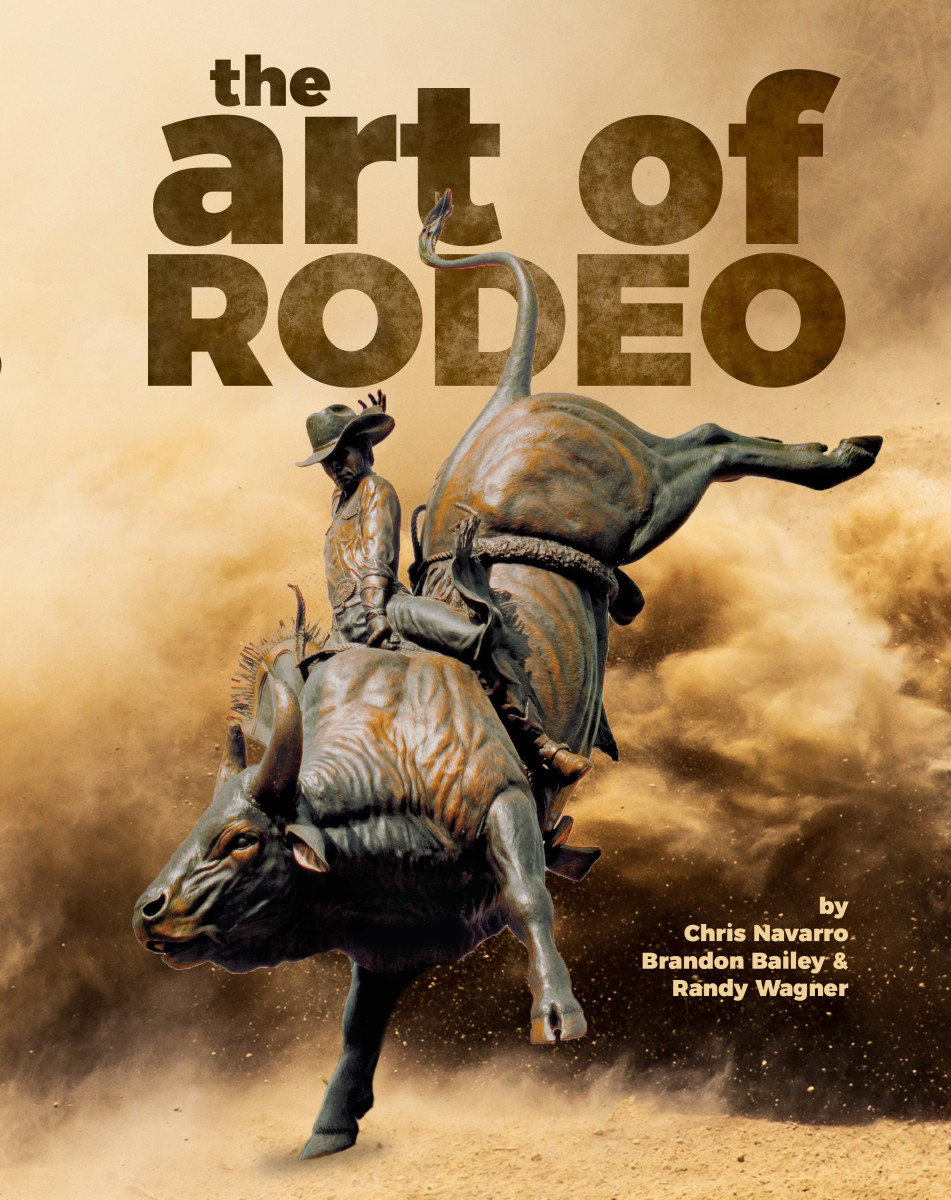

In the latest testament to his rodeo roots, Navarro has just self-published his fourth book, The Art of Rodeo. Themed around his home-state’s iconic Cheyenne Frontier Days, the 272-page hard-bound tome includes 600 images of artwork from Navarro and two more artists: photographer Randy Watson and painter Brandon Bailey.

The book is made of 19 chapters, paying homage to each rodeo sport—including the women’s ranch bronc riding that returned to Cheyenne in 2019 after a 90-plus year hiatus—as well as the history of the rodeo and the greats who elevated its lore and fame, including the legendary Lane Frost—the subject of a monumental sculpture in which Navarro takes great pride.

“That was my first big public monument I ever did,” Navarro said of the piece, titled “Champion Lane Frost.” “I was 36 years old when I started that. Cheyenne turned me down, at first, when I made my proposal. I go to their big, board meeting and I set [my model of the sculpture] down and lay out how we could raise the money by selling the small ones to make the big ones. They called me in the next few days and said, ‘We’re gonna pass on your idea. It’s a good idea, but we have this new wing we’re building onto the grandstand.’”

In response, Navarro committed to raising all the money on his own, so long as CFD would build the pedestal. And he did. For $1,000, donors to the Lane Frost Memorial Fund could support the project, get their name on a plaque at the base of the monument, and receive one of 250 18-inch miniature bronzes cast in the likeness of the monument, available only by donating.

But raising money for the monument was just the beginning of the challenges Navarro would face, including the premature death of his 66-year-old father, shortly after he began the build of the 15-foot sculpture. When he was able to resume the task, he made steady progress, but yet another challenge remained.

“Just when I have it almost 100% done, it goes up in a fire,” said Navarro, who was conducting the build in the foundry in Cody, Wyoming, since the work didn’t fit in his own studio. “I’m sleeping in the foundry. I call 911, I jump out of a second-story window. I had Lane’s championship buckle and a lot of his personal stuff.

“An electric heater was warming up clay for finishing the base the next day and it set the clay on fire because it’s oil-based and it got too hot. It did about $40,000 worth of damage to the building, and ruined some of Lane’s stuff. I ordered clay the next day and finished like a week before the dedication. So that piece is always going to mean something to me because of all the stuff I went through.”

Navarro’s work and The Art of Rodeo is currently on exhibit in the James Gallery of the Phippen Museum in Scottsdale, Arizona, through April 25, 2021.