Depending on who you ask, rodeo got its start in a dusty field in Prescott, Ariz., in 1888 or in the sagebrush of Deer Trail, Colo., in 1869. Since then, cowboys and cowgirls have been on a quest to form a more perfect union of sorts between competitors, fans, stock contractors and the inevitable administrators and other role players who go along with running a successful organization. And much like the ongoing pursuit of a more perfect union in these 50 states, it hasn’t been easy.

Rodeo, at its core, is one of the last holdouts of the Old West. In a world where kids know how to swipe their iPads long before they’d ever think to do a chore let alone swing a rope, rodeo is struggling to figure out how to stay relevant.

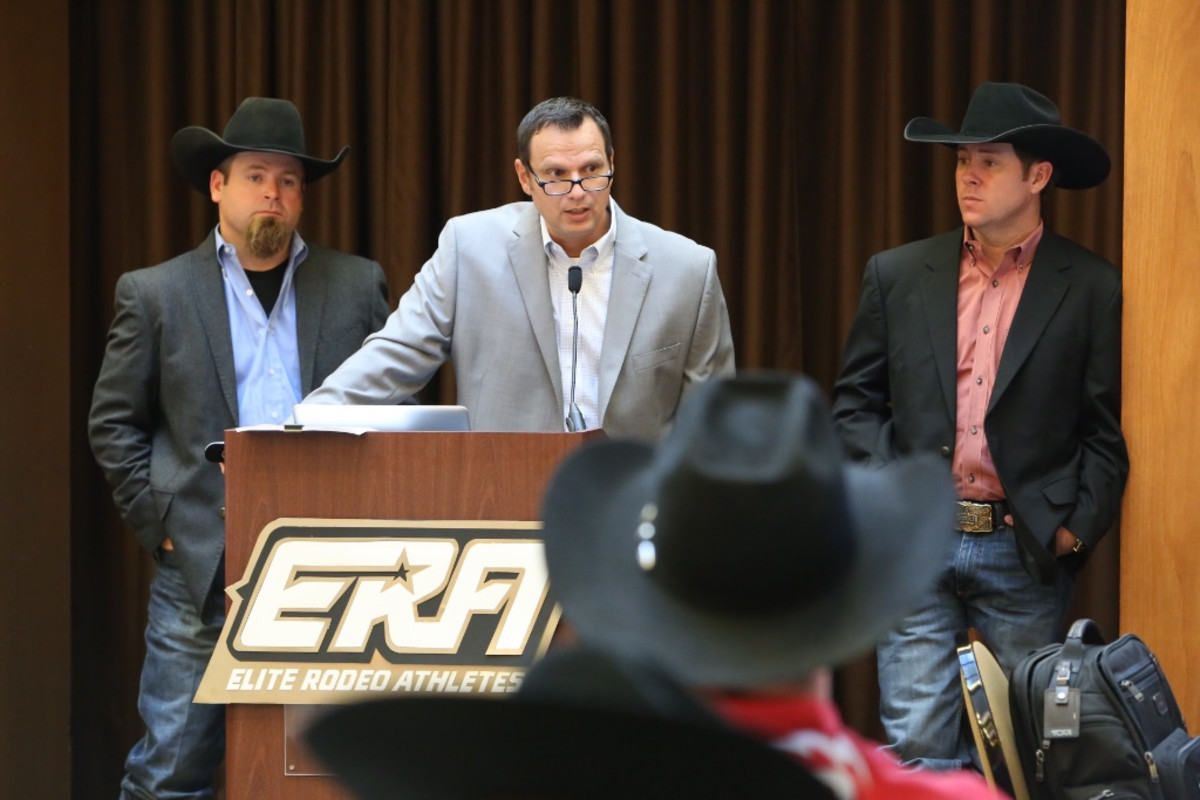

With the recent rise and subsequent stumble of the Elite Rodeo Athletes and the cowboys’ return to the Professional Rodeo Cowboys Association, perhaps now is as good a time as ever to revisit where the sport can grow and what the industry is doing right to make that growth possible.

Numbers game

There’s no getting around it: there are fewer cowboys trying to make a living traveling up and down the road than there were 20 years ago. PRCA membership declined to 4,782 in 2015* from its peak of 7,403 in 1999—a 35-percent decrease. The number of PRCA-sanctioned rodeos dropped from its peak of 798 in 1991 to 624 by 2015—a 21-percent decline. The 1990s also saw a larger number of cowboys competing on their permits to try to become cardholders, peaking at 4,197 in 1997 and dropping to 1,784 in 2015, representing a 57-percent drop.

“Economically, the problems we are aware of are that it’s a pretty tough way to make a living,” PRCA Commissioner Karl Stressman said. “The people who really want to be in it are in it, and the people who want to dabble in it are not involved. I can tell you we certainly need to be recruiting out of the Little Britches, high school and college ranks so that we continue to build the future.”

While overall prize money is up since the membership peak in 1999 from $31,062,127 to $46,349,782, when those numbers are adjusted for inflation, payout is up about $1.2 million, or 2.6 percent over 16 years.

Compare that to the growth rate in other sports, like tennis and golf, said Randy Bernard, the man behind RFD-TV’s The American and current consultant for the Elite Rodeo Athletes.

“The first rodeo ever was Prescott in 1889, and the payout was $860,” Bernard said. “The U.S. Open in golf wasn’t established for seven years after that, and it paid out only $335. The US Open in tennis was established in 1881 and had no prize money until 1961. But they understood the power in developing stars and understanding their fan base. Payout at the U.S. Open in golf has compounded annually at 8.9 percent a year. Their total prize money today is $7,846,000. Look at tennis. Tennis understood the power of having participants. If you think you’re good enough, you can qualify for the U.S. Open. Today, the annual prize money at the U.S. Open in tennis is $27 million. If the sport would have done a great job of building stars and awareness and keeping excitement levels up and keeping with television, that payout at Prescott could be $12,955,000 had it compounded annually at the same rate as golf. But today it pays $252,000.”

Looking even further back, and not including payout at the Wrangler National Finals Rodeo, the top 24 rodeos ranked by prize money in 1981 paid out some $3,452,721, which, adjusted for inflation, comes to $9,944,748 in 2016 dollars. In 1990, the top 24 rodeos paid out $4,406,682—adjusted for inflation that’s $8,432,020. The ’90s saw gains in membership and number of rodeos nationwide, and the payout of the top 24 rodeos reflected that. In 2000, with rodeo still reeling from a successful decade, rodeo paid cowboys and cowgirls $7,066,790, adjusted for inflation coming to $10,060,825.89. And in 2015, the top 24 rodeos paid $11,311,795, with a slight adjustment for inflation making it $11,325,369 in 2016. Those are a lot of numbers to take in, but what that means is that cowboys trying to make the WNFR saw a bump of $1,380,621, or about 12 percent, in 34 years, at their top-tier rodeos.

These figures don’t include the PRCA’s Xtreme Bulls division, and they obviously don’t account for the new money available to cowboys at Professional Bull Riders’ events, big jackpot ropings and CINCH rodeos, among other big-money events.

The WNFR paid $4.42 million in 1999, when the PRCA membership was at its peak, and adjusted for inflation that’s $6.4 million. The PRCA paid out $10 million at the WNFR this year, and even Stressman says that’s not enough for rodeo’s best athletes.

“If you look at the Wrangler National Finals as far as the payout, it sounds like that’s a lot of money,” Stressman said. “Tyler Waguespack wins $218,000 or so and wins the Top Gun and a new pickup. Is $300,000 enough for the top guy? Absolutely not. It’s just not sufficient for the best in his class. The best of the best, the most highly decorated cowboy in history is in the $400,000 range annually. I’ve got to believe that someone who sits at the end of the bench for the Denver Nuggets makes that.”

To be precise, 23-time World Champ Trevor Brazile holds the top nine single-season earnings records, ranging from $329,924 in 2006 to $518,011 in 2015. Brazile has earned $6,079,528 in his ProRodeo career—while Tiger Woods, the greatest golfer in the same timeframe, has earned $110,061,012 in professional prize money.

So when Brazile and fellow (former) ERA athletes branched off in 2016 to start the new association, they did so with the hopes that the payouts would increase and the expenses would decrease. In its first year, though, the ERA paid out $1 million in Dallas at its world championship, a drop from the $3 million initially promoted.

Challenges

When 80 top cowboys and cowgirls set off in 2016 with their own solution to help build rodeo’s payout and prominence with the ERA, they sought to make superstars out of the sport’s best while bringing a high-end production to fans in person and on Fox Sports 2. But organizers quickly ran into road bumps filling seats and garnering sponsorship.

“I was surprised to see how few people actually know even the most well-known cowboys and cowgirls outside of die-hard rodeo fans,” Bobby Mote, four-time world champion bareback rider and interim-ERA president said. “Rodeo has been sold as entertainment only—not as athlete personalities. For that reason, today you couldn’t go to a major market and promote a rodeo with any of the most well-known athletes. Unless there is an effort to promote the best in the sport, then a rodeo has a better chance of selling tickets with a monkey riding a dog than Trevor Brazile or Fallon Taylor.”

That problem is one the PRCA has long-understood, Stressman said, and that affects rodeo committees’ ability to charge a higher price for tickets, which would increase their payouts.

“We don’t have the opportunity to expand the ticket pricing,” Stressman said. “Even the NFR, look at the pricing at the NFR. The most expensive front-row ticket is a $300 seat per night. Sure that sounds like a lot of money, but you can probably go to a rodeo and buy a $6 or $7 general admission ticket to get in and see the same events you see at the Wrangler National Finals, but the ticket pricing doesn’t reflect that. Your community sets your ticket pricing. Say we have a 3,800-seat venue, you set the ticket pricing at $6. It doesn’t take long to do that math. Then you find out what that transfers into as far as paying the production costs of the rodeo, and then putting the added money in for the cowboys. Sponsorship is a part of that—but local sponsorships don’t bring in a ton of money for the committees. Sometimes it just doesn’t pencil very well to keep increasing the payouts.”

The ERA started on the foundation that by promising the biggest names in rodeo, the association could command a higher price for admission. Tickets at the ERA Rodeo in Nampa, Idaho, started at $20 and went up to $77, while the Snake River Stampede, also in Nampa, Idaho, sells tickets starting at $9.25 and topping out at $34.50. That didn’t work, and the ERA didn’t get the numbers they needed to make the model work.

“I do still feel like rodeo should be more than a $10 circus ticket,” said Brazile. ”Whether it was ready for it all at once, I don’t know. When you have to sell a sport like a circus, something is fundamentally wrong because then you’re telling me there’s no difference between an ERA rodeo, a PRCA rodeo or a county fair anywhere in Texas. Maybe we need to do things as an industry to fix that. We need to do it progressively, not all at once.”

While cowboys like Brazile and Mote found themselves entrenched in day-to-day operations of the ERA’s eight-rodeo schedule in 2016, doing so in the PRCA is a different ball game with the grueling 75-or-so rodeos needed to qualify for the WNFR. Trying to rodeo full-time and participate in the PRCA operation comes with its own challenges, Stressman said.

“The athletes don’t have time to be part of the solution sometimes because this industry is so interesting as far as the number of events they have to go to in order to qualify for the Finals,” Stressman said. “These are the full-time guys trying to get to the Wrangler National Finals. They don’t have any choice but to rodeo, rodeo, rodeo…And it’s hard on them. And if anybody thinks we don’t recognize that—we do recognize that.”

Mote, who took over running the ERA June 13, 2016, when the cowboys and cowgirls fired their management team, has learned a lot about what it takes to change rodeo from the inside out, and agrees that cowboys managing an association presents challenges.

“I’m just tired of hearing people complain without coming up with a solution,” Mote said. “When I rodeoed, I was one of them. There are people in leadership in the PRCA, who, if they had support, the whole association would benefit. Everyone has their own agenda, and it makes it hard when you’re in leadership. It makes it hard to get out front and take the arrows if nobody is willing to support you and follow you. You look at the list of men and women who have been behind change and who have been willing to make sacrifices for the greater good, they’ve gone above and beyond.”

Cowboys and cowgirls in the ERA showed up days before an event to help promote the rodeo in each city, and Mote said he was proud of the athletes’ involvement, proving that there are enough leaders in rodeo to try to make positive change.

But that positive change was hard to create with a divided industry—a critical lesson everyone involved learned in 2016.

“They shouldn’t have tried to alienate the PRCA,” Bernard said. “It’s where your legacy and heritage is. There’s no way you can start it and create enemies from the start. All boats rise on a high tide. They should have been going to PRCA rodeos. The first thing I asked them to do was to tell the cowboys to rodeo and be relevant or nobody will remember who they are in five years.”

“In hindsight, I wish so many things would have been done differently,” Brazile added. “Hindsight, I wish we’d have had a deal made with the PRCA Board of Directors so we weren’t put in this position.”

And the ERA representatives weren’t alone.

“Somebody asked me the other day, if I had a clean slate, what I would do differently,” Stressman said. “This showed us that there’s some opportunity in working together.”

The ERA further alienated competitors and fans when they decided who could and couldn’t compete at their rodeos, Bernard said.

“They needed a great qualification system to allow anybody who thought they were the best to get in,” Bernard said. “They had done themselves no justice not having a ladder for competitors to reach the top.”

The ERA also had problems with leadership, Mote added, that affected the association’s ability to change quickly.

“We didn’t have enough leadership of substance that the industry had confidence in,” Mote said. “What’s good for one group another group doesn’t like, and it all goes back to people’s personal agendas.”

Unity

The ERA will not have any rodeos in 2017, and instead will spend the year under new ownership re-examining its structure and its approach to growing the sport. So with most of professional rodeo coming back together under the PRCA’s umbrella, leaders are looking at how and where the sport should move forward.

“Our goal is to bring rodeo together rather than fraction it,” Mote said. “The former (ERA) management had it in their minds that they were going to take over and make people make a choice. I don’t think you can do it that way, and it’s not healthy and proven not to work. Whatever happens moving forward, my goal in five years is that the industry is unified.”

To move forward to best serve the association’s membership, Stressman believes rodeo must figure out a system of tiers to serve everyone from the weekend warrior to the WNFR cowboys.

“How do we tier rodeo?” Stressman said. “How do we make the tiers best for the whole operation? You can’t lose the people in the middle. You have to be very careful as to how you start tiering it. We’ve only been talking about it for 80 years, but I do think that tiering is mandatory.”

Two-time world champion heeler Walt Woodard, who has held a PRCA card since 1975, agrees that the PRCA has to walk that line.

“When you have a meeting for the best guys in the world, they want 40 rodeos just for us,” Woodard said. “But when you make decisions for rodeo, it has to be for everyone. The general membership—the circuit guy—doesn’t like being excluded from the elite rodeos. He can’t go to San Juan (Capistrano) or San Antonio. If you want to have rodeos for the best in the world, that’s not a realistic thing that benefits all of the rodeos. The PRCA has started to have rodeos with the circuit guy in mind. Now the circuit finals money counts (toward the PRCA world standings). A circuit guy places in a few rounds and wins the average at his circuit finals, and now all of a sudden he has $7,000 won. Then he goes to the All-American and gets tapped off and wins $15,000 there. Now he has $23,000 won. People think those rodeos can’t count, but you can’t exclude them from San Juan and San Antone and not give them something back. The PRCA is making decisions for all of the contestants. That’s how you build the circuits and make them better.”

Each tier of rodeo needs to be aware of different, yet important goals, Bernard said.

“There’s a huge place for small, medium and large rodeos,” Bernard said. “Each one has such different, specific goals that need to be looked at. Small and medium rodeos should focus on significant community involvement and be helping the community in positive ways.”

Rodeo needs to work harder to tap into its grassroot support as well, Bernard said, pointing to the success RFD-TV’s The American had in working with the Better Barrel Races and United States Team Roping Championships for its qualifiers.

“What I had with The American that the PRCA didn’t have was access to hit send on an email to 50,000 with the BBR and USTRC membership base, to bring people up to speed and to push out messages,” Bernard said. The BBR and USTRC could be utilized to help individual committees produce their slacks, too, Bernard said.

Study Abroad

The PRCA is also looking to expand its reach to Mexico and Brazil in 2017, a process that began when PRCA leadership met with the Mexican Rodeo Federation’s leadership in San Antonio three years ago and resulted in 150 Mexican cowboys buying their permits in 2016 and a payout of $11,815 at the Mexican Tour Finals this October in Cuauhtemoc, Mexico.

“Our job is to expand rodeo when it’s appropriate,” Stressman said. “We want to be a world-wide organization. We do business with Canada, and they’re very close to the PRCA. Their leadership right now is strong and getting stronger. Mexico was an interesting fit. It will take some time to grow, partly because of the culture. Rodeo is rodeo, no matter where you place it. There are lots of fans who watch the NFR. I was at a team roping in Mexico and it looks like just any other roping. They’ll qualify to the RNCFR in Kissimmee, and that brings an international flair to Kissimmee, which they’re used to there. I just signed a deal to do a few rodeos in Brazil, and if you look at Marcos (Costa) and Junior (Nogueira), you can see how well they’re represented here. We will have our first event in Brazil this spring. We’re also looking at Australia. My goal is to grow the PRCA. We need to make it better and we need to expand the brand in the PRCA. We need to put something together that will make sense. We need to be cautious as we grow but we need to put the brand worldwide.”

Red States

Bernard, who has been helping Mote figure out the next steps for the ERA, said that rodeo needs to first do a better job reaching the rural American marketplace before it looks to branch out.

“There are 80 million people who live in rural America,” Bernard said. “There are 46 million Hispanics and 38 or 40 million blacks. Yet everyone tries to reach the Hispanic audience as the lifestyle that companies are trying to tap into. But nobody cares about the rural lifestyle and trying to reach them, or they would be spending more money on RFD-TV. I hear these companies getting affiliated with rodeo talking about being more mainstream, but they’re not in the small towns and doing a good job of it. I could take Trevor Brazile to a street corner in Fort Worth, Texas, and five out of 10 people wouldn’t recognize him.”

Rodeo must build its top cowboys up as superstars to those in rural America, Bernard argued, like NASCAR did in its early days.

“To have stars, you have to focus on where you are,” Bernard said. “And rodeo needs to be focusing on rural America. NASCAR did a tremendous job of focusing on its core market in Georgia, Tennessee and Florida—the South. Once they were selling hundreds and thousands of tickets there, then they started having a stronger brand across the country. The rest is history. That’s a large part in thanks to TNN. Their core audience was the Red States. That’s what they did a fantastic job on. Everything else was a bonus, if New York or Chicago viewers tuned in that was a bonus. They understood and built their audience and fan base within the rural and Western lifestyle.”

Committee-level change

Perhaps nobody understands the fan base of each of the 600-or-so rodeos better than the committees themselves, who each have to balance their budget and meet their individual goals each year, Stressman said. The PRCA simply sanctions each of these rodeos and doesn’t individually run most of them, limiting the association’s ability to enforce top-down change, Stressman said.

“We don’t control the money paid out in rodeo for the most part,” Stressman said. “The committees provide that. Any time the committees struggle to obtain sponsorship, it’s difficult to increase the dollars. That’s the control issue—how much the committees can afford to pay. Their expenses are going up. They just want to be able to balance the books at the end of the rodeo. It’s not an easy thing to try to correct. There’s 625 individual businesses trying to operate under the sanctioning of the PRCA, and they control the purse strings.”

Salt Lake City’s Days of ’47 Rodeo, which was an ERA rodeo in 2016, is back in the PRCA this year and putting up $2 million for this year’s record purse. That’s a good thing for the contestants, but it beckons back to the discussion of creating a tier-system for rodeo.

“One of the things that’s concerning to the contestants is paying that much money to a single person at one of those rodeos catapults them almost instantly into the Wrangler National Finals,” Stressman said. “You have to say that’s part of what we’re going to do, or we aren’t going to do that at the PRCA. We want that $2 million rodeo. We want San Antonio. We want the relationship with Houston or Calgary back the way it was eight or 10 years ago because it’s good for the sport, and it’s certainly good for the contestants. But, there’s more than 400 of the 600 total rodeos that pay less than $30,000. So put it into perspective, as you look at 5,000 contestants going down the road, as you begin to divide that money up, it gets pretty skinny. And really that’s the portrait that’s out there, whether you want to believe it or not.”