If ever there was a horse that we all figured couldn’t die, it was Jackyl. He’s rumored to have cheated death once, escaping the kill pen before his career even started and ending up with some Oklahoma ropers. The unregistered dun gelding traveled more miles than most rodeo cowboys themselves, and he won more money than any other horse in the history of the sport.

In the end, though, Father Time always gets his way, and Jim Ross Cooper laid to rest the great heel horse this past December at almost 30 years old.

“He got to where he was having too much trouble getting around,” Cooper said. “We took him to the vet, and there was nothing more they could do. So we made the decision to put him down. He was the best. Jackyl’s stats speak for themselves. It was a dream come true to be able to own and ride him. He was so good that I’ll forever compare every new horse I ride to Jackyl. I don’t think I’ll ever ride a better one.”

[READ MORE: Jackyl, The Two-Million-Dollar Heart]

[READ MORE: Jade Corkill’s Jackyl is the 2013 Spin To Win Rodeo Heel Horse of the Year]

While Jackyl may be gone, his legacy remains in the careers of some of the greatest heelers in the history of the sport. A 15-year-old Travis Graves rode Jackyl in 1998, after buying him from Oklahoma roper Ryan Miller.

“He’ll go down as one of the greatest horses of all time,” Graves said. “He was dirty tough, he could run, he stopped really good and he was just a winner. If you had to draw a heel horse, with his conformation, he’s what you’d draw. He was gritty, and he loved heeling. He really did. He was good at all of it, really. He was probably the best heel horse of all time at the NFR. He was good even when I had him all those years ago. He had a lot of slide—over the years, that slide went away and it was more of a stop-the-run kind of deal.”

Graves’ dad sold him to Tyler Magnus, who passed him along to Kory Koontz—who on the horse won three Wildfire Open to the World titles.

“What I think, that was so great about that horse was, not just one person did good on him,” Koontz said. “He was a winner with every different person that had him, everybody that borrowed him, everybody that owned him. He was always successful. He was what it means to be a winner. When I had him from day one, he didn’t do everything perfect, but I won on him. The day I tried him, I roped a lot of steers by two feet and won first and third on him.”

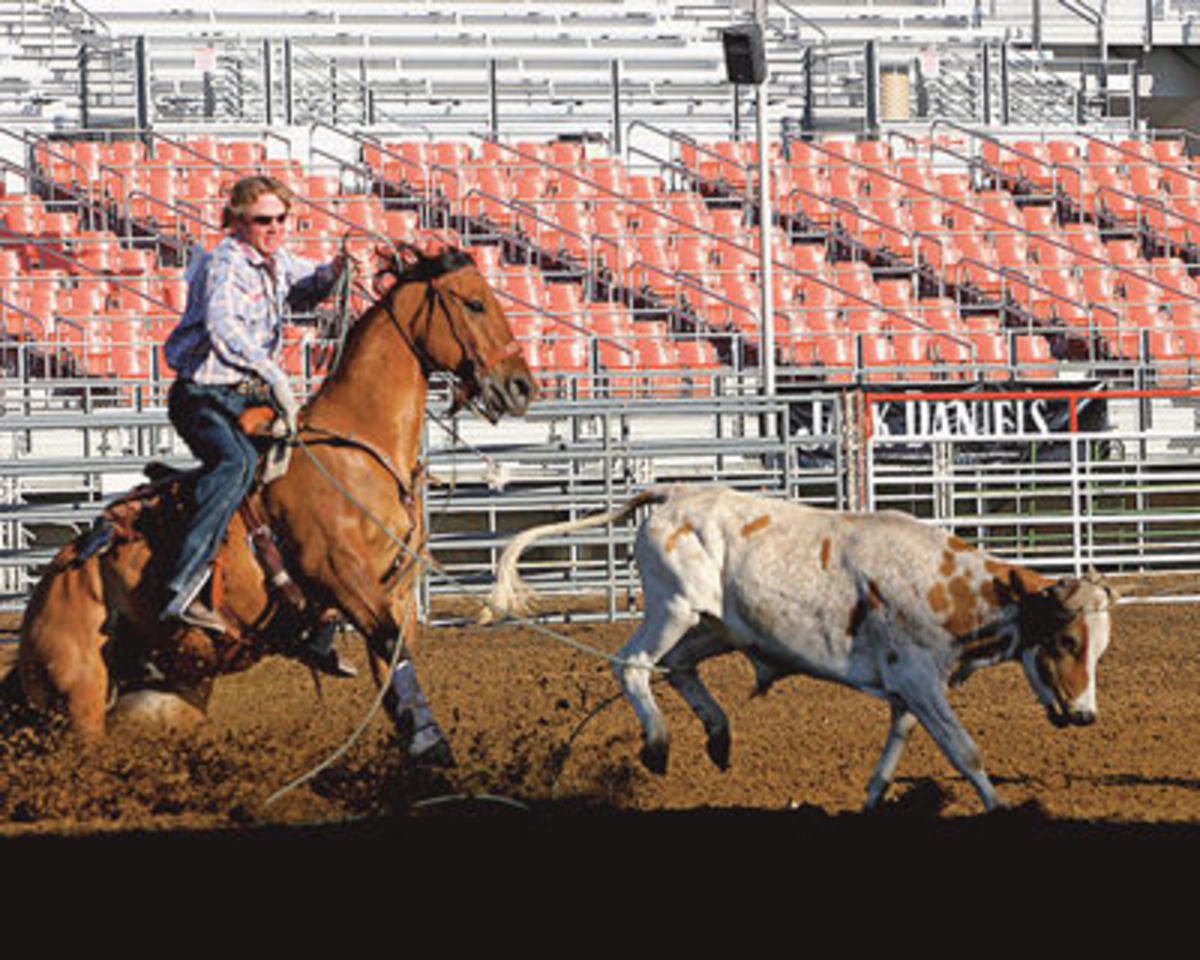

In those days, Jackyl could act like a stud from time to time, occasionally reared out of the box, would stomp dogs for crossing into his pen and buddied up to other horses. But he became rock solid, and Koontz qualified for four NFRs on the Jackyl and won the California Rodeo Salinas on his back.

Koontz let Michael Jones ride him at the 2004 NFR behind Clay Tryan, where they won the average and set an NFR earnings record.

“He didn’t even practice on him for the National Finals,” Koontz remembered. “Now Michael was that confident and that talented, but it also said a lot for that horse the way he worked.”

“He was a game changer,” Jones added. “The amount of guys with different styles, who could ride and win on him against the best in the world, shows how diverse he was. He loved the sport. He loved to win.”

Jones bought Jackyl in 2006, and Allen Bach borrowed him that year to win a world title. Jones won the George Strait on him in 2008, and he eventually used him to doctor wheat cattle on when he slowed down rodeoing. Jackyl got a few years’ rest before Jade Corkill called Jones out of the blue before the 2012 Wrangler National Finals Rodeo when his two-time PRCA/AQHA Horse of the Year Caveman went down with injury.

“I had ridden Jackyl a couple times before I called Michael,” Corkill said. “I rode him with Travis (Tryan) when Michael left him at our house in Fallon during Reno. When Travis would get on Walt, I’d get on Jackyl and heel for him. I had this weird feeling in the fall of 2012. I didn’t know if Jackyl was sound, if he’d been getting rode at all. I called Michael out of the blue. I had a feeling if I could get him and ride him in Las Vegas. I had a real true feeling I could win the World if I had that horse there. That was in October. So long story short, I took him in October, and I was the Columbia River Circuit that year. I rode him there at the Circuit Finals and won it. And then in Las Vegas, where Kaleb Driggers and I won the first round with him. He meant a lot in the short time I had him. He got me what I was trying to get my whole life.”

Corkill rode Jackyl on and off again in 2013, and in Round 1 of the NFR that year. Corkill’s oldest son Colby was barely 2 years old back then, and the old gelding—long-since softened from his outlaw days when Koontz owned him—fostered Colby’s love for roping.

“He meant a lot in the short time I had him,” Corkill said. “Colby loved to ride him. He rode him all the time. He was a cool horse to have around. Not many horses get that famous, and your odds of getting to own them are even smaller. He was so humanlike. He knew for real what was going on. He wanted to go and wanted to be rode. If I caught Switchblade and walked by his pen, he’d start biting the chain on his gate.”

Corkill sold Jackyl—already 24—to Cooper, who won The Daddy of ‘Em All on him, behind perhaps one of the fastest head horses of all time, Brandon Beers’ Tevo.

“At that point, it seemed like you could maybe ride him at smaller arenas, where he doesn’t have to run as much or do as much or be athletic,” Koontz said. “But Jim Ross rides him at the biggest arena, on the longest score, with huge steers, and he hammers three right on the corner and the horse works great and wins the rodeo. That defines how much heart that horse has.”

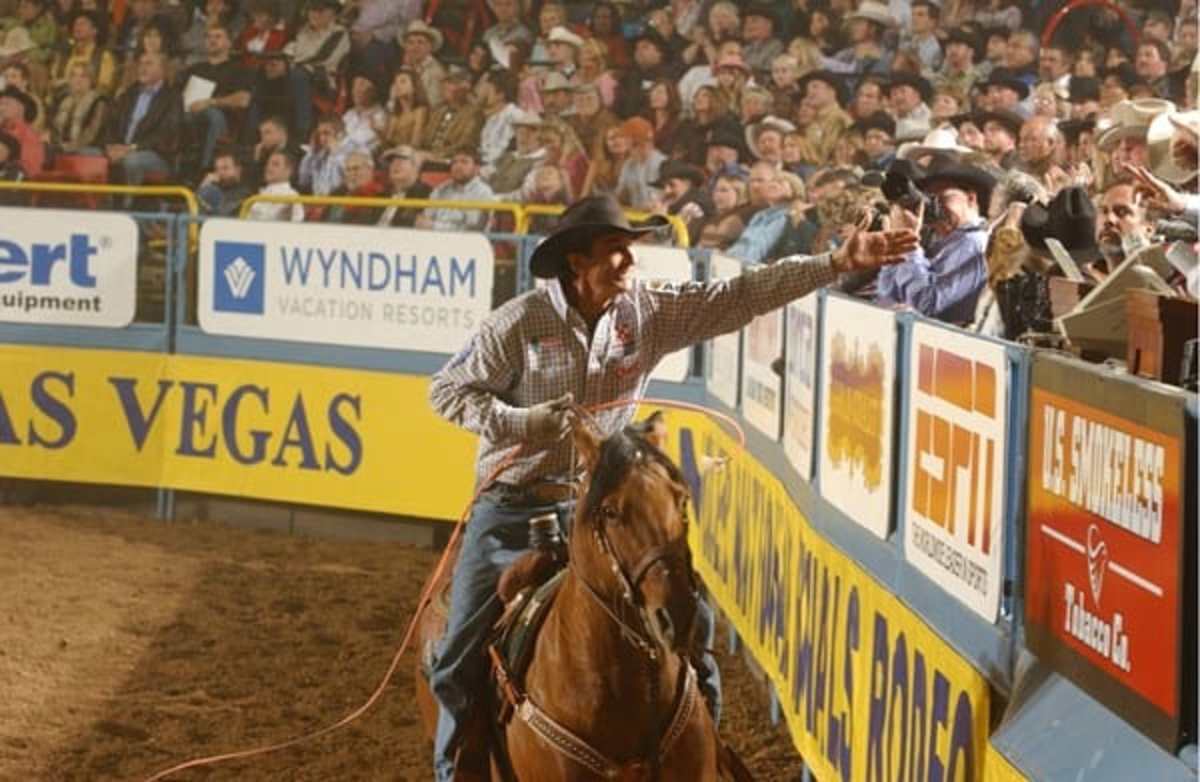

Cooper made the NFR that year—2014—and Jackyl left the Thomas & Mack with the day money on his last appearance in the City of Lights.

“We were all back there getting ready to rope, and I had to catch to win the world,” Corkill said. “But you can’t hear the announcer saying Brandon’s name or Jim’s name—he’s just talking about Jackyl. And I wasn’t thinking about catching my steer anymore. I was sitting in the tunnel thinking about that horse. Nobody thought he’d get old and die. We thought he’d have just dropped dead at the top of his game—that night, all I could think was that Jackyl probably had a heart attack in the tunnel.

“There will never be another one like him,” Corkill continued. “I got to be a part of his career—he wasn’t a part of mine. I feel more lucky to say that than anything.” TRJ