The American frontier was a time and place when rules didn’t apply and scores were settled with shootouts. But that had nothing on jackpotting in the 1970s.

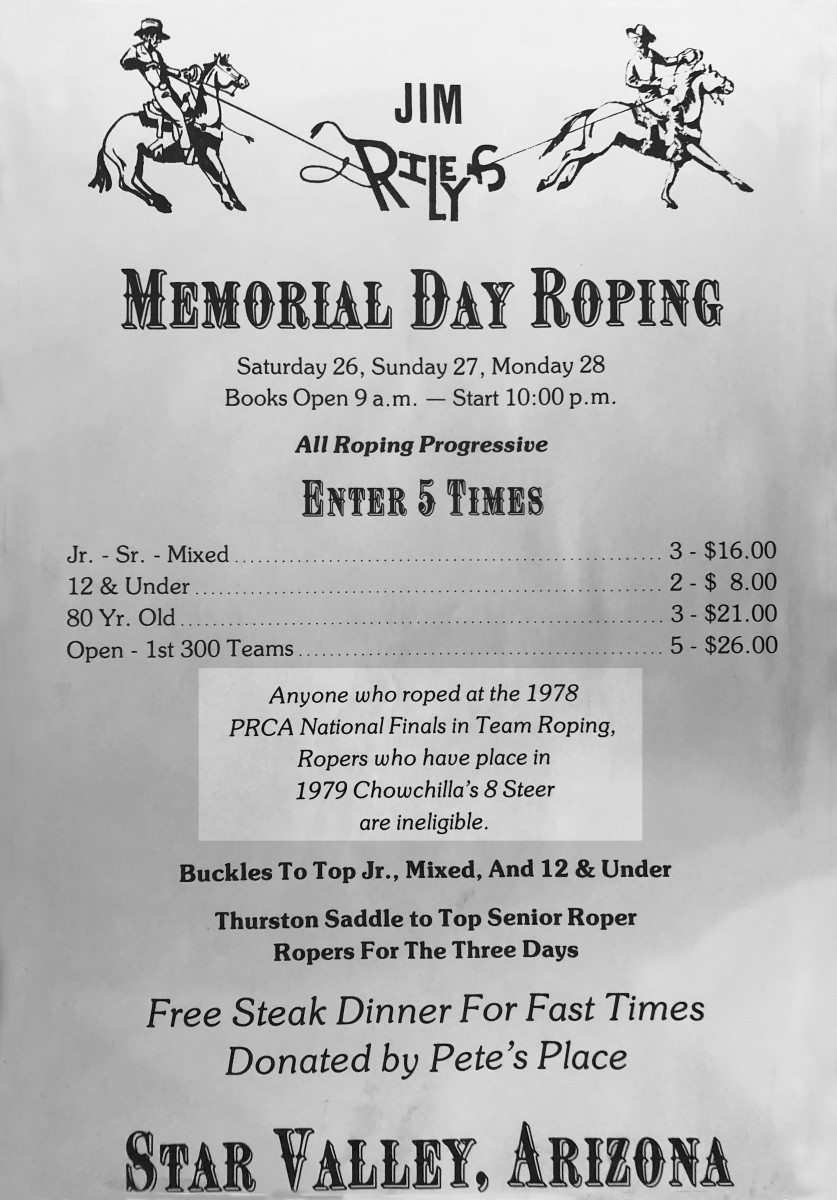

To quote the best of the best, team roping was the “Wild West.” It was a cat-and-mouse game between producers trying to ban the handiest guys and those guys finding ways to get entered. Remember, rodeos paid hardly anything. Jackpots were the only way to come out in the black.

“I’ll never forget,” said eventual two-time world champion header John Miller, “the rodeo was here in Phoenix, so Ace Berry and Jim Watson and Jack Rasco and I load up and go out to a jackpot in Laveen. As we pulled up to the arena, Bill Roer was right there and said, ‘I don’t even need you guys to unload your horses. You can’t rope here.’ That was in March 1968. It was the first time I knew of anybody getting barred,” added Miller. “It was kind of a shock.”

BEGINNING OF THE END

In the late 1980s, early forms of today’s handicapping system revolutionized team roping. Before that, most guys figured the sport would not survive outside rodeo.

Back when John Lennon was alive and the Watergate fallout was forcing President Nixon out, California was to team roping what Texas is now to rodeo. They’d been dallying longer out there, because until the late 1960s, Arizona was still mostly team tying. And the West Coasters had plenty of rodeos at which to sharpen their skills.

The “prunies” were so tough that, out of the first 40 NFR average buckles given out, only six didn’t go home to California. But rodeos paid so little that after heading at the 1978–79 NFRs, Brian Burrows of Los Angeles spent the next dozen years only jackpotting (he won Chowchilla three different times).

“I’d invited Rickey Green to my first NFR, and he didn’t have enough money to buy a jack for his trailer,” recalled Burrows, 65. “He cut off the end of his finger hooking his trailer on to go to Oklahoma City.”

Besides, the Oakdale 10-Steer paid about $4,000 to win—when a new pickup cost about $4,500. Guys like Walt Woodard remarked that it made your whole year, winning one of those ropings. At the time, there wasn’t a single jackpot you pulled into, with Supertramp playing on your radio, that wasn’t at least a five-header, if not an eight- or 10-steer (they might have a three-steer pre-roping). That increased the odds for better ropers. Not only that, but the PRCA had just scrapped the old go-twice entry system to enter-once. It drove the best guys to jackpot—and that was the downfall.

“By the 1980s, I thought this team roping deal was about over with,” said Larry Goss, a former BFI champion from Oregon who roped at three NFRs in the 1960s and ’70s. “Producers had to make up rules as they went along, because dominant guys would go pitch a shut-out and win all the money. That’s why I figured this thing was short lived.”

Eventual five-time world champion Leo Camarillo, along with his peers, totally understood.

“You go to all the expense to put on a jackpot and pay for the cattle, the help, the arena rental, and try to make it work,” said Camarillo, 73. “Then these guys come in and run all your numbers away. It was a tough way to make a living anyway, and guys would tell the producer they weren’t roping because a certain someone was in the parking lot. That put it on the producer to go up to a stranger and say, ‘I’m so-and-so and I don’t know your name, but I understand you rope good and you’re not allowed to rope here because all these other people won’t rope against you.”

SUBTERFUGE ENSUES

Producers looked for ways to even the field. First they decided to ban the PRCA’s top 15. But that wasn’t fool-proof. Burrows remembers when Gary Mauw of Chowchilla would win all three holes in every roping. Producers got where they’d only let him go once or twice at an enter-up roping. He didn’t rodeo, so their rule of “no top 15” didn’t apply to him.

“Now this is hearsay,” said Ozzie Gillum, who trained and sold the gold-buckle buckskin, Ike, to Clay O’Brien Cooper. “But Les Jones had an arena over there in southern California and he wouldn’t let Mauw rope. That is, unless Mauw would go next door and rent a dude horse to ride out of the dude string. I heard he didn’t win much in the first or second round, but by the third, he could get the horse around the corner and get him a check.”

Goss recalls that Gene O’Brien was the first producer to bar him.

“I told him when Clay was coming up, ‘You did me that way, pretty soon you’re going to have to do your kid that way,’” recalled Goss, 70. “And he had to. His kid was ruining his ropings.”

The best lasso artists understood why producers didn’t want them in the parking lot, but still, hustling commenced. “Champ” remembers that era—he came in on the end of it before he won seven gold buckles.

“You didn’t want to get to the roping early,” Cooper recalled. “You rolled in there just before the books closed, so you could catch them with all their money up.”

J.B. Getzwiler, 64, could catch “a million in a row” according to Burrows, and went on to rope at the NFR. He vividly remembers those days.

“You wanted to be anonymous; you didn’t want any fame,” Getzwiler explained. “You needed the element of surprise.”

There were no cell phones, but there were CB radios.

“One of the weaker ropers of the group would go in ahead while the others waited a few miles down the road,” recalled Bob Feist, who traveled with one of the first living-quarters trailers. “You could enter until the end of the first round. So the first guy would wait and then get on the CB and tell the other guys to come on in and enter.”

That worked until producers got wise to it and rushed to start the second go. Also, Feist said, you didn’t want to pull into one of those little jackpots with California plates. Ropers would actually change to out-of-state plates on their vehicles.

“I saw producers try to ban people who’d won over $5,000, not allow anyone with PRCA cards, make you only go once and even make you switch ends,” recalled eventual two-time NFR average winner Denny Watkins of Bakersfield. “It was a lot harder to make a living than people think.”

LAYING OUT

Watkins was 19 in 1975 when he was barred by Louie Tavaglione from the 10-steer in Riverside, along with Ken Luman, Jim Rodriguez Jr. and Leo Camarillo.

“We put a lawsuit against him because it was a right-to-work state,” Watkins recalled. “We thought we could win. We lost. Our attorney told us why. That was Louie’s own arena and he had a right to do whatever he wanted. It wasn’t commercial. We knew we were in trouble from then on.”

Producers had another idea. They made their ropings only for “non-winners.” That meant you could never have placed in the average at the big ropings in Oakdale, Riverside, Chowchilla, Las Vegas or Reno.

“I remember J.B. Getzwiler and I were about 30 seconds in the lead after four or five at Oakdale one year, but we knew we didn’t want to place,” said Burrows. “You couldn’t even place eighth in the average and still get into those other jackpots. So at Oakdale, we treated it like eight rodeo one-headers. We’d win a couple of rounds and stay out of the average. It’s crazy; at the best ropings in the world, you never rode your good horses.

Camarillo recalls there was “this woman out in Ceres who kept track of what everybody won,” and they started having “category ropings” like an under-$500 roping, an under-$1,000, etc., all the way to $10,000. That’s how the American Cowboy Team Roping Association started.

“I had a fit when they started that,” recalled Watkins. “I was like, ’what are you doing? People are going to lay out and stay under that $2,000 so they can go to one roping and win more! It’s not good for the sport.’ It took the ‘want to’ right out of people. Honestly, if not for the USTRC, I really think the sport would have died. Think about all the tack companies and rope companies and jackpots and schools that wouldn’t have happened. Because not everyone is going to rodeo. Not everyone can rodeo.”

CLASSIFICATION SAVES THE DAY

Even before producers began classifying with dollars won, Cooper said he was never barred completely in Arizona—just limited to go-once.

“Lots of ropings just kind of dwindled down because of that,” he recalled.

West Coast ropers being shut down migrated east to New Mexico, Texas and the Rocky Mountain states where they could go to some good jackpots and rodeos. Getzwiler said they’d follow the seasons, hitting California in the spring, the northwest and mountain states in summer and fall, and back to Arizona in winter. But it took out-of-area producers even less time to throw new rules at the interlopers.

“I’d won first, second and third at a roping in The Dalles, Oregon,” Goss recalled, “and Tommy Norton said, ‘You can’t come to my ropings.’ I hired an attorney, who was going to padlock the gates before his next roping started. But the attorney made it clear that if I lost, I’d be responsible for all that money lost. I had a great case, but I didn’t want to risk so much.”

A Rock-Solid Office: The Men and Women Behind the Entry Office

Burrows said they came up with rules like “Montana ropers only,” or you had to be from Oregon.

Bill King of Wyoming’s famed King Ropes remembers visits to Sheridan from California’s best in the 1970s and early ’80s, and likened them to Arizona’s Bucky and Tiny Bradford.

“They’d just lurk around and take everybody’s money,” said King, laughing. “They’d wait in the weeds. I remember Rickey Green was only a teenager when he came here to a big roping. He got 86’d.”

Goss will never forget the day he went to a roping in Denver and climbed the block wall at the side of the box to watch the score. “Get off there,” the producer told him. When Goss said he was just watching, he was told they wouldn’t allow him to do that.

The most talented team ropers were scorned, barred, kicked out. Jackpots floundered and nearly disappeared forever. But now, 30 years after Denny Gentry organized national classifications, you’ll never watch someone win all the holes in the roping. Better yet, you’ll be able to rope no matter how good you get.

Thanks to the hustling spirits of the die-hards from the Pacific coast—and a few innovative producers—team roping survived the Wild West.