Very rarely in rodeo history has a world team roping titlist come from money. Sure, it would have been nice to have the funding to roll up in a fancy rig full of the best horses money can buy. But in my line of work—in my lifetime that started with growing up at rodeos and ropings, and stayed there—the lion’s share of the legends in our cowboy sport have been rooted in humble beginnings. Excuses, no. Sweat equity, yes. Bottom line, the elite few who reach legend status earn it and are unstoppable because they outwork everybody else and won’t take no for an answer.

No Excuses, Just Hard Work

To take it from the top, 26-time World Champion Cowboy Trevor Brazile—whose unmatched gold buckle collection contains all-around (14), team roping (1), tie-down roping (3) and steer roping (8) buckles—was not born with wealth and a bottomless expense account. The Texas teen actually drove Momma Glenda’s baby blue Volkswagen Rabbit to high school, and his first rodeo rig was a two-tone brown gas-guzzling super cab Ford with a rusted-out two-horse trailer in tow. The skinny kid was constantly stranded on the side of the road pouring water into that old, overheated bucket of bolts, and caught a lot of early-day rides to rodeos, so he could actually get there. Junior rodeo barrel racing checks were not beneath him, either, because he sold those all-around saddles to upgrade his rig.

Trevor’s more of a role model than an advice giver, and he likes to keep life simple.

“A person who’s good at making excuses is rarely good at anything else,” he says. “Don’t complain. Work harder.”

I’ll throw in an interesting fun fact here for you young guns. Home school was not an option until recent times. Every icon included here got his happy ass home and back to school come Monday morning. And that often meant an all-night drive to be at that desk by the first bell. Eight-time Champ of the World Speed Williams knows what I’m talking about here.

“I did not come from money, but I don’t look at it that way, because I had a mother and a father who were willing to do whatever it took,” said Ken Speed Williams, whose dad Ken Eugene Williams was a horse trader who worked every event in rodeo and also worked as a pickup man to earn extra money. “My mom would take me anywhere, but her rules were we had to be back for school by 8 o’clock Monday morning.

“We did not own the place where we lived, we rented. But my folks put in every effort to raise a champion. My dad paid people’s fees to rope with me, hauled them in the truck with us and mounted them on his horses. Mom tried to get me a job at the feed store, and Dad said, ‘No, his job is to go to school and rope.’ I was taught and prepared to be a world champion. He wanted me to be a world champion heeler, and fought me for three years about the heading. But gold buckles were the goal.

“We didn’t have a lot of money, but my mother and father did whatever it took. I don’t think you make it at this level without some kind of help, and people stepped up and helped me along the way. There was no trust fund, but there was help when I needed it. People loaned me the money to buy Viper and Bob interest-free. That changed my life. People let me use their trucks and trailers until I was financially able to buy my own. Friends who believed in me helped me, and every guy who’s made it has a story like that. We did not get there alone.”

The Cost of Chasing a Dream

Before Speed and Rich (Skelton, who also grew up with modest means; his dad owned a flooring store), there was Jake and Clay.

“You didn’t see many people with money back in the day,” Barnes said. “It was beg, borrow and steal to get down the road. Back when we were rodeoing, there were four guys in a truck splitting the fuel and hotel rooms. There were no living quarters trailers, and you didn’t think twice about two guys sharing a bed or somebody sleeping on the floor. That’s just the way it was. The school of hard knocks is what made most of us. I grew up in a small town in New Mexico. I wasn’t groomed to be a world champion, like some kids are today. I just loved to rope.

“I had zero direction when I flew the nest to go to college on a rodeo scholarship. I left home with a truck I bought myself on payments, and two horses in a two-horse trailer. I had zero money. I made the high school finals every year, but because of economics only got to go my senior year. I heeled for my cousin Gary Armitage at the high school finals up in Helena, Montana. We got to go that year, because somebody did a fundraiser for the kids from New Mexico who made it.

“At 17, I was making a living at jackpots, first-partnering with Dan Fisher and second-partnering with Don Beasley. Tee Woolman was first-partnering with Don, and Dan second. When I was 19, I bought my own single-wide mobile home on a lot in Portales, New Mexico, where I went to college, with money I won at jackpots and amateur rodeos. I think I paid $7,500 for that place, and I used it as a rental when I started pro rodeoing. It wasn’t like I could call home and ask for money. That never crossed my mind, because it was not an option. I was always frugal with my money. There was no playing around and wasting it.”

Earning Every Loop

Cooper was born in Arizona, and raised from age 3 in Southern California. His stepdad, Gene O’Brien, was “a jack of all trades. He worked as a wrangler in the movie business when there was work, and was an outrider at the racetrack leading horses to the starting gates. He shod horses. He sold and butchered livestock. He put on jackpots.

“Through the blessing of being picked to be in (the John Wayne movie) ‘The Cowboys,’ I pursued being in the movies for five years, from when I was 10 to 15 years old,” Clay continued. “During that time I was working, my heart was wanting to rope. That was my dream—to rope and rodeo. But I was able to save up $30,000 working in the movies, which ended up being the down payment on my first place. I left home and moved to Arizona at 16, and started jackpot roping. I lived with Jimbo and Maryanne Wales for a year, then moved in with Tom Cox for a year. When I was 18, Beth (Beach) and I eloped, and I bought my first place in Gilbert, Arizona.

“I started working when I was 10 years old, and never stopped. I look back on my life and see that movie opportunity as such a blessing. God used all the different things to make my dream of roping for a living come true. I didn’t know I was poor growing up, so to me money was irrelevant. Money’s not a value. Value is treating people right, being proud of what you stand for and working hard.

“You can be rich or poor—have everything or have nothing—and without values and morals, you don’t have much. I’ve seen kids ruined by silver spoons, because they didn’t have to grind. And I’ve seen kids with money who made something of that blessing, because they were raised right. So I think it’s the structure of family values you grow up with, and not the money, that makes or breaks you.”

Woolman grew up in a family of six—in a three-bedroom house with three sisters. He shared a room with his baby sister, Oowala. Dad Oliver owned the full-service Phillips 66 filling station. After working at a bank for years, Mom Wilma worked as the bookkeeper at the Farmers and Ranchers Livestock Auction sale barn in their hometown of Vinita, Oklahoma.

“I didn’t get paid, but I worked for my dad and grandfather as a kid,” Tee remembers. “My mom took me places, because my dad was home working all the time. We didn’t have a lot of money, but we had food on the table.

“There are only a handful of guys from every era who actually rope for a living. Everything I have was paid for with a nylon rope. We rodeoed in a very different time than what it’s like today. We didn’t have sponsor patches on our shirts. Roping’s a lot more corporate now, and it’s on TV all the time, where it didn’t used to be. Whether you grow up with money or not, I think you appreciate success more if you earn it the old-fashioned way. You’re also more respectable to people.

“I always wanted to be the best, so I had to work hard. I had some natural talent, but I worked harder, because I wanted to be the best there was. Silver spoon or not, you have to put your mind to it and work, or you’ll never make it. And I always wanted to be a cowboy more than a roper. Cowboys have manners, and respect for people and horses. A lot of respect has been lost, and that’s not progress. I have no respect for people who think everybody owes them because they can rope really well. My roping got me where I am today, but I hope I will always have enough respect to have manners, and say yes sir and no ma’am.”

“Making it the hard way makes you better.”

Clay Tryan owns three gold heading buckles. But his road to the top wasn’t paved with gold, either.

“Most of the best guys didn’t come from money,” he said. “Making it the hard way makes you better. There’s a difference between having to win and not. When you have to win, every steer matters more. My dad (National Finals Rodeo heeler Dennis Tryan) did whatever he could for my brothers (Travis and Brady) and me. We weren’t rolling in it, but we had decent horses.

“More people have nice stuff now than when I started roping for a living. The circles I grew up jackpotting in were not like that. Early in my rodeo career they didn’t even have team roping at all the big rodeos, and there was no social media. There was the Rodeo Sports News and the Ropers Sports News. That was it, and they didn’t have team roping at rodeos like Fort Worth and Cheyenne.

“In my eyes, the only advantage to having money behind you is the ability to buy good horses. Money doesn’t buy you the ability to rope. When you back in there, it’s about who ropes the best. If you got good with or without money, good for you for getting good.”

Lasting Lessons

At 69, Walt Woodard is defying Father Time. He’s still winning on roping’s biggest stages, and against ropers a fraction of his age. So no, you won’t hear Walt whining or asking for any age-related handicaps. He doesn’t want or need them.

“My dad (Sheldon) shod horses, and my mom (Audrey) cleaned houses,” Walt said. “I grew up on one acre in French Camp, California, with no arena. We had a homemade horse trailer my dad and Bruce Fisher built.”

Did growing up without a silver spoon make Walt stronger?

“Yes, it does everyone,” he said. “Anyone who grows up like I did is mentally stronger and tougher. My dad didn’t say, ‘Here you go.’ He told me, ‘You’ve got to figure it out.’ So I did.”

Do team ropers with trust funds have an advantage, or no?

“Yes, it’s a tremendous, simple, one-word advantage—horsepower,” Woodard said. “Clay Tryan said something profound years ago when he said headers should get 60 percent of the money, because heelers can ride the horse they high school rodeoed on. It was a pretty profound concept that a team should take 10 percent of their winnings and set it aside for horses. There’s a lot of truth to that. It’s a constant battle.”

The Camarillo boys changed the heeling game when they started timing steers and roping them out of the air instead of laying a trap. Brothers Leo and Jerold, who often heeled for cousin Reg, were raised with modest means. Dad Ralph ran ranches on the Central Coast of California, and Mom Pilar cooked for hire at places like Andersen’s Pea Soup in Buellton, and Mattei’s Tavern in Los Olivos.

“We didn’t have a lot of money, and that’s why we wanted to rope,” Jerold Camarillo said. “We figured we could make more money roping than working. There was always a competition between brothers with Leo and I. We always matched each other. If one of us did something, then the other tried to do it better. If we didn’t win, we had nothing to fall back on. Leo and I had to win.

“I don’t think today’s young guys can grasp how different rodeoing was in our day. There were no cell phones, so we had to pull over and put quarters in a pay phone to enter and find out when we were up. We couldn’t get directions on our phones, because we didn’t have phones. We kept an Atlas (map) in the truck, and figured it out.

“Guys rope, then head to the next one now. We had to stay after the rodeo to pick up our paycheck, so we could get to the next one. There was no paying entry fees online or getting paid by direct deposit on your phone, so a lot of rodeo secretaries cashed a lot of cowboys’ checks all the time.”

Jerold and Leo went to school, but they did a lot of daydreaming and ran a million steers in their minds in class.

“I barely made it through high school, but I could figure out the payoff for a roping or rodeo in my head in nothing flat,” Jerold grinned. “I knew what 40-30-20-10(%) paid to the penny. So many young ropers are homeschooled now, but in our day, homeschooling was unheard of. You had to go to school. Period.

“I wouldn’t change a thing about my life. It’s been a great one. The only thing I wish my dad would have done is put a golf club in my hand instead of a damn rope. The golfers made millions, and here we were working for hundreds. Leo and I had the dedication of Tiger Woods. How would my life have gone if instead of roping pop bottles and winning my first jackpot at 7, I’d have been swinging a golf club?”

More Than Money: What Really Makes a Champion

Rich or poor, cutting corners will never cut it.

“It’s no easy thing if you want to make the big time,” Camarillo said. “You have to work at it. If you want to just rope for fun, great. To each his own. That was never our mindset, but then again, losing was never an option for us. If we wanted to rodeo, we had to win to keep going.

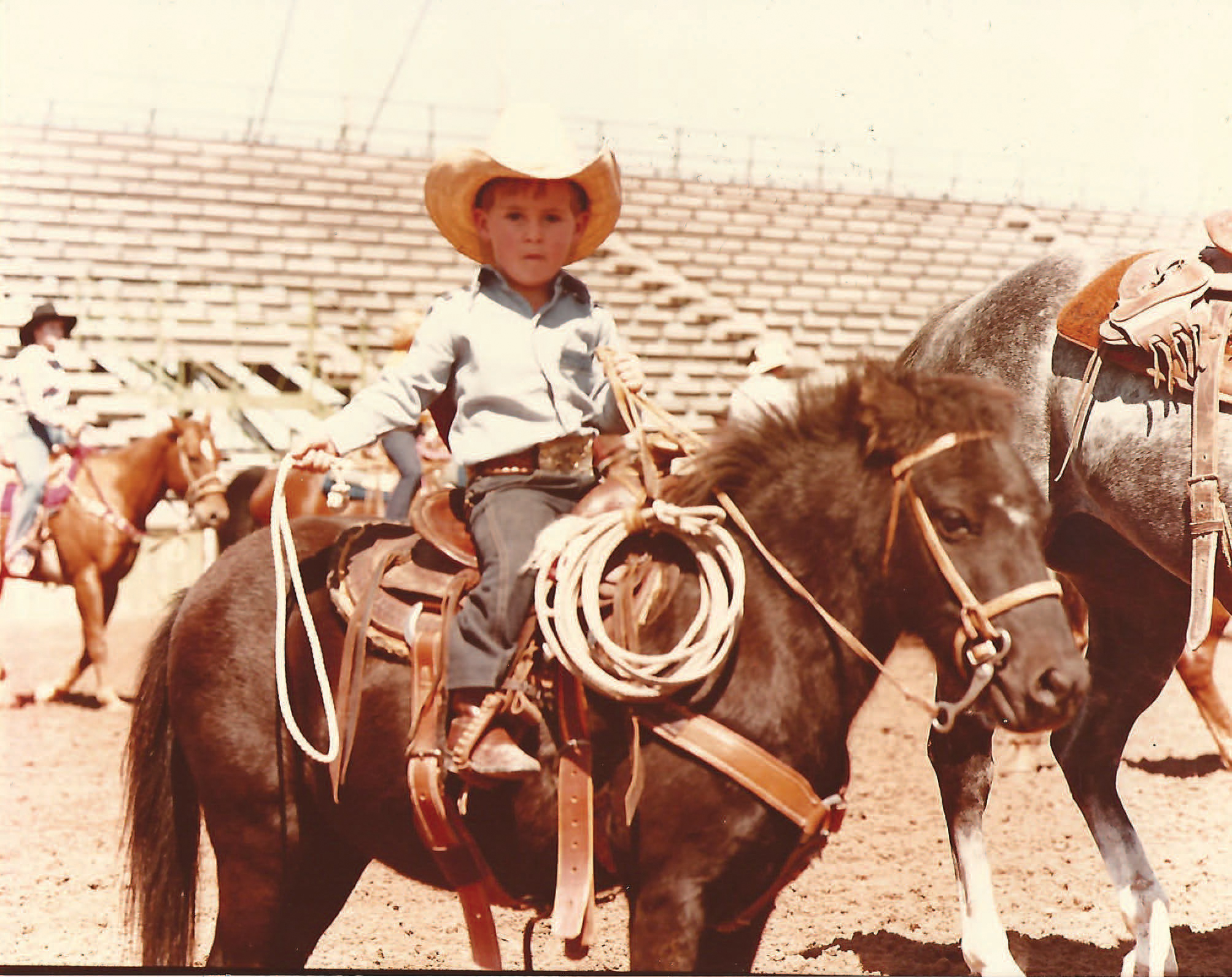

“I remember one time way back when Speed Williams’ dad came to one of our roping schools. Little Speedy was there working the chutes and turning out cattle for us. Then when we turned out a steer, he’d try to rope him on his pony. He was determined from a very young age. Look at how that worked out for him. No one hands it to the champions. They work for it, and they earn it. End of story.”

—TRJ—