Driving through the looming granite rocks of Texas Canyon on Arizona’s Interstate 10 in early January 2008, a 24-year-old Colter Todd passed seven-time world champion Jake Barnes’ rig somewhere between Tucson and Willcox. They were both heading to the Sandhills Stock Show and Rodeo in Odessa, Texas, ready to start the new PRCA rodeo season. Todd, fresh off his second WNFR qualification with Cesar de la Cruz, picked up the phone to check in with Jake, who was roping with Clay O’Brien Cooper again that year.

“I made a comment, just talking, that 20 years from now, we’d still be making this same trip to Odessa,” Jake, who joined the PRCA in 1980, said. “I don’t really know why I made that comment, but maybe that planted a seed for him.”

No, he wouldn’t, Colter told Jake. Jake laughed it off, and reassured Colter that he would.

“I said the same thing over again,” Todd, now 34 and ranching in Willcox, said. “I wasn’t going to be driving to Odessa in 20 years.”

Colter Todd was born in Willcox, at his family’s ranch, where four generations of Todds still live today. He went to the JoAnne Todd Christian School, started by his grandmother years earlier, through eighth grade with his two brothers, Dustin and Tayrell, and sister, Savannah. His parents, Larrie (everyone calls him Rooster) and Lori, ran cows and rodeoed and home schooled the kids through high school. Colter was horseback any time they weren’t studying or going to church. And from a very young age, Colter had his mind made up on a few uncompromising ideals: he wanted to make the WNFR, and he wanted to raise a family back home on the ranch in Willcox.

“I worked hard when I was in school, so I could be out of school as much as possible,” Colter said. “My heart’s desire was both school and cowboying, and that’s what I did.”

Colter grew up close to his grandfather, Larry, now 81, from whom Rooster believes Colter got his decisiveness.

“When he said he was going to do something, that was it from the very start,” Rooster said. “If he was going to do something, he was going to do it. He would get done with the junior rodeo and he’d have trouble with calf roping or team roping, and we’d get home at 11:00 or 12:00 at night, and he’d go out to the barn and rope the dummy and work at it for another two hours. That’s how his mind works. I always knew deep down he didn’t want to be a rodeo cowboy, he wanted to be a ranching cowboy. He wanted a place of his own and cattle. That was his ultimate dream, but along the way he wanted to go to the NFR.”

Lori, a two-time Ram National Circuit Finals Rodeo qualifier, ran barrels with Cesar’s mother, Zenaida Olivar, and the future NFR partners met in the dirt parking lots of barrel racing jackpots, roping everything that walked.

“When a lot of your friends were trying to get you in trouble, Colter would always try to keep you out of trouble,” Cesar, now 34 with nine WNFR qualifications to his name, said. “I’d go visit the Todds quite a bit from the time I was 13 until I was 17 or 18. They were such a great family, they’d take anybody. They always were branding, moving cattle. They’d keep me out of trouble. It was really easy to get in trouble in South Tucson. You couldn’t get in trouble at Colter’s unless it was horse trouble, and that was usually not the worst thing that could happen.”

When Colter and Cesar weren’t roping goats in the arena they built at the ranch, they were junior rodeoing, where Colter met his future wife, Carly. Carly was born in Montana, but her parents got sick of ranching in the snow and moved the family to Cave Creek, Arizona, when she was just 2. Her dad shod horses and eventually opened the famed Dynamite Horseman’s Supply. Handy even then, Carly barrel raced, goat tied, pole bended, breakawayed, and cut.

Carly was a year and a half younger than Colter, and the duo started dating early in high school. Colter, who heeled in his younger days, won the Arizona High School Rodeo title in 2002, behind neighbor Tanner Resor. But as high school came to an end, Colter was ready for a change from the Arizona cacti and desert sunsets.

A famous family acquaintance, Mel Potter—acclaimed AQHA breeder, former PRCA board member, and father of world champion barrel racer Sherry Cervi—stepped in to make that adventure possible.

“If you ever wanted to write a story of how God works in somebody’s life, I’d be the one to write about,” Colter said. “Mel had a hired guy to ride colts, and he quit. He called his daughter, Jolynn, who called my dad. We knew them from training horses. Dad came to me and wanted to know if I wanted to work for Mel at their ranch in Wisconsin. And that sounded like a great new world and opportunity. I called him and he said, ‘How soon can you get here?’ That was a Tuesday. I said I would be ready when I finished my schooling that week, and he had a red eye flight for me Monday morning at 4 a.m.”

Sherry, already a two-time world champ then, was off the rodeo trail that year after the sudden death of her husband, Mike Cervi, Jr., in a plane crash the year before.

“I got to visit with Sherry a lot during that time about what a person needed to be successful,” Colter said. “I also remember I asked her if I could get married young and really make it work.”

Sherry told him that yes, of course he could, and after making a long-distance relationship work with Carly over his summers in Wisconsin, he popped the question. Carly went to the National High School Finals Rodeo that summer engaged, and they were married at the First Baptist Church in Willcox that next March.

Colter and Carly went back to the Potters’ place in Wisconsin the next summer. He had joined the PRCA, and he heeled for Mel and other friends in the Great Lakes Circuit. He also got to meet a young heeler named Cory Petska while working for the Potters, too, who he’d eventually buddy with to make three WNFRs.

“I’d never been around somebody that was so ranchy, that’s for dang sure,” Cory laughed. “It was cowboy boots and cowboy hats every time we went to town, to the movies, anything. I’d never met anybody as punchy as Colter. He loved roping, and he loved ranching, and he knew what he wanted to do. He wanted to make the Finals and then start his family.”

Colter got his first PRCA win in 2004 at the Heart of the North Rodeo in Spooner, Wisconsin, and picked up wins at the Glenwood City Championship and the Lincoln County Rodeo Days, both in Wisconsin. At the same time, Colter came across the horse that would carry him to three WNFR qualifications and most of his $423,140 in career earnings.

“Mel really wanted me to ride one of the horses he raised. I told him to pick me one, and we’d make him. That was the horse we called Frisco, and he was registered as PC Lonewood Ike. I just wanted a horse under me. I was heeling mostly. I won the #9 Shootout at the U.S. Finals on him back then in the old number system. Then I went to heading.”

With their first baby on the way, in 2005 Colter swapped to the head side for good and started entering rodeos with his junior rodeo pal, Cesar. Colter had Frisco and Cesar had his iconic Johnny Ringo, and they hit the road for their first year of full-time ProRodeo competition.

“He was the reason I was so successful early in my career,” Cesar said. “We had the same goals. We wanted to win rodeos, make the Finals, and live our childhood dream. I was really spoiled in my career having him as my header first. Even then, after just one year on the head side, he was one of the top headers going.”

Colter and Cesar’s style matched the rodeo young-guns they were: aggressive.

“I liked to win first,” Colter admitted. “Partly because I was always into the trinkets. It was just fun.”

That first year, Colter finished 22 in the world with $32,220 won, and Cesar was 19 with $33,149. Colter roped with Idaho’s Ryan Powell in the #15 Shoot-Out at the USTRC’s National Finals of Team Roping in Oklahoma City that year and won the average and the short-go fast time, picking up $38,900 a man.

“Some people are over aggressive and try to do things they can’t do,” Ryan said. “Colter’s the kind of guy who, whenever he did something, he was pretty sure he could get it done. When I entered that roping with him, I thought if I did my job every time, then we’d win. I let him take care of the special stuff that day, and we did good.”

Carly and a very young Madilyn came on the road when they could, leaving their place in Marana, Arizona, to spend time with Colter. Carly, who still rodeoed to make the Turquoise Circuit Finals as often as she could, had horses at home and went to the Todd family’s Willcox ranch to visit on weekends.

“I didn’t go to Texas often in the winter,” Carly said. “He’d come home as much as he could during that time. My favorite thing would be California in the spring and the Northwest in the fall, because we stayed with such great people. In July and all that, I just didn’t go much. But Madilyn and I would show up and surprise him when she was little.”

Colter and Cesar got on a roll in 2006. They notched the biggest win of their career so far at the Cheyenne (Wyoming) Frontier Days, with Frisco standing out in that setup—punching their tickets to their first WNFR.

“Walking into the Thomas & Mack to break in the steers, that was a cool moment,” Carly said. “It really sinks in that it all paid off. Watching him compete and getting to be there, because he had worked so hard and really deserved it, it was really special.”

They placed in two WNFR rounds, winning the eighth round. They’d also won the US Open at the USTRC’s National Finals of Team Roping that year, each banking $50,000.

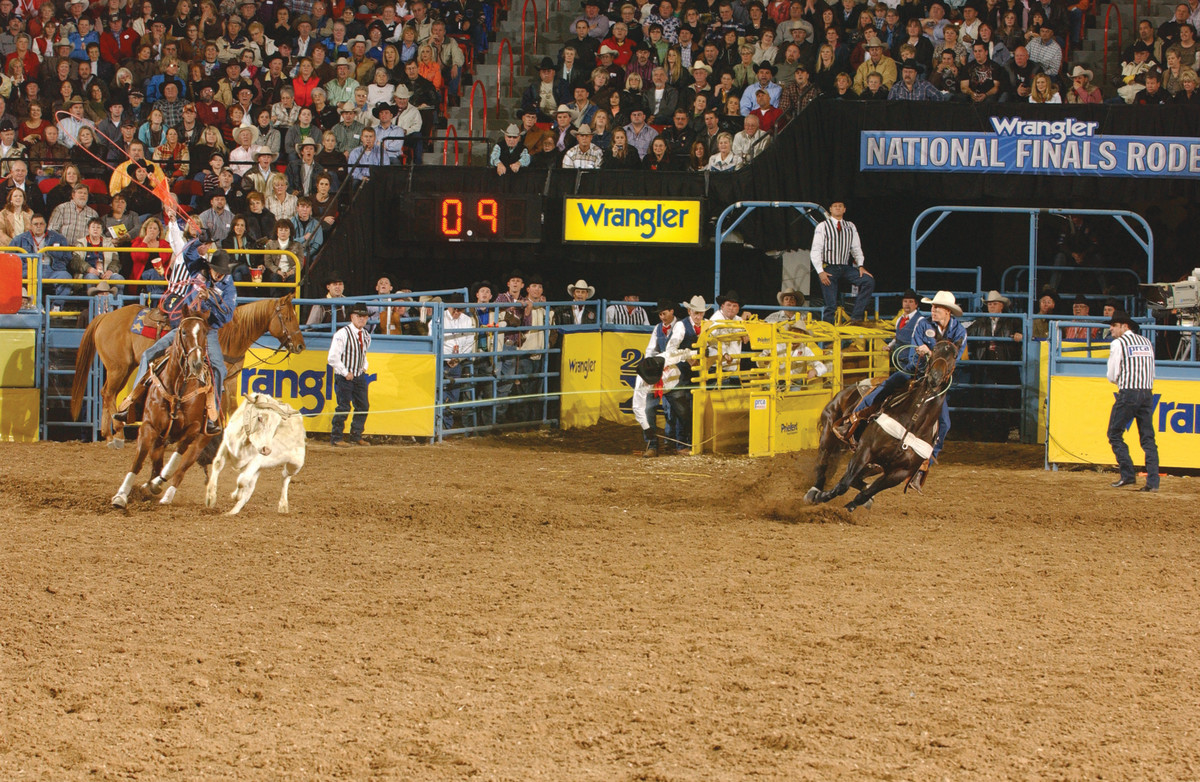

In 2007, Todd and de la Cruz gave themselves a fighting chance at a world title and had another great year jackpotting. They won the Wildfire Open to the World in Salado, Texas, and the WestStar Open in Ellensburg, Washington. They won Rounds 6 and 9 at the WNFR, and earned $93,958 at the Finals alone, finishing third and second in the PRCA world standings, respectively.

By the time Colter made that fateful phone call to Jake in the winter of 2008, the rodeo road had worn on the young cowboy. He had his first son on the way, and his daughter was growing like a weed. He’d made his mind up to notch a few WNFR qualifications and earn a little money with a rope to start his ranch, and he’d done that. Colter, a devout Christian, began talking to God about where he should go from here.

When Colter and Carly married four years earlier, at 20 and 18, they’d never discussed how long they’d rodeo. Lying in bed one night after the spring rodeos, Colter turned to Carly and said he was thinking about being done and moving to the family’s place in Willcox. Carly, who’d not grown up ranching, was a bit wide eyed.

“We were young enough when we got married that we didn’t really talk about where we saw ourselves,” Carly said “And then, at the moment, we were rodeoing, we had a place in Marana, and it was just what we were doing. I asked him what he wanted to do, and he said he wanted to raise his kids on the ranch. I was really set on him finishing the year. I didn’t want him to quit before the end of the year.”

He and Cesar were outside the top 15 when they got on a plane from Cheyenne to Salinas, California, in July. They weren’t placing when they left The Daddy, and were needing a few big hits before the end of the year if they wanted a shot at their third trip to the WNFR. Sitting on that plane, a road-weary Colter looked out the window, closed his eyes, and asked God for an answer.

“I needed a clear-cut answer: Should I quit?” Colter said. “I wanted to quit and really be done. My desire to travel was completely gone. I said, that’s it. It’s true about any job. If you don’t love that job, don’t do it. I don’t care what it is. My desire to be out there, it was gone. It lost the pizzazz. If you don’t have that drive in any sport, whether it be the win or the loss or the travel, if the will to drive all night to the next one is gone, man, do something else.”

The next day, at Salinas, Colter sat down with Cesar to talk about his decision. But he was worried Cesar wouldn’t believe him, and wouldn’t get in a hurry to find a new, top-notch header.

“He said he was missing his family an awful lot,” Cesar said. “The traveling never was good for him. The roping part, he loved that. He told me at Salinas he’d give me the rest of the year, he’d give it his all, but whether we made the Finals or not, that was his last year. I knew he was serious.”

The duo’s goodbye tour ran through the Wrangler ProRodeo Tour Championships in Dallas, where they tied the then-world-record with a 3.5-second run in the semifinals and won the finals. They won the Puyallup (Washington) ProRodeo and headed to their third WNFR.

They placed in three rounds at the Finals heading into Round 10, and both Todd and Carly felt at peace before Todd backed into the box on the brown mare he called Spice, who he’d ridden in the Thomas & Mack the last two years. Cesar had found a new partner—a new, young kid and friend of Colter’s from Seba Dalkai, Arizona, named Derrick Begay, who rode a Paint horse and had just made his first WNFR with Cesar’s uncle, Victor Aros, and wanted to buy Colter’s Spice, too. And Colter and Carly had managed to save enough to get started on a place next to Rooster and Lori in Willcox. So in Round 10, he could really let his hair down.

“The very last steer I ran in the Thomas & Mack, I won the round,” Colter said of that $16,767-a-man payday. “I got to go out with a bang. I wasn’t one of those elite great headers. It was just fun. We did a lot of good, and we won a lot of rodeos.”

“Colter always instilled in me—rodeo is a rollercoaster ride for sure—that the tough times are tough,” Carly added. “At the end of the day, it was a God-given opportunity and gift, but this isn’t what defines us. I just said, ‘OK, we’ll do it.’ Looking back now, I know God was leading me. I’m so grateful that he did decide to come home and raise the kids on the ranch.”

They made the six-hour drive home from Las Vegas to Marana the next day, packed up their house in just two days, and headed to Willcox, where they’d be 22 miles from the nearest store, 16 of those miles on dirt roads.

“I didn’t know what I’d do but I knew where I wanted to be,” Todd said. “I slowly got a managing job for a guy that neighbored my folks. And it just went from there and it’s been a dream.

“I had a lot of people calling to go to the winter rodeos. People would try to talk me into it. Your word is about all you have in this life. And I would love to be remembered as somebody whose word is good. I said I was quitting, and I said I was done. If I were to go to any rodeo, especially the big ones, San Antone, Houston, and win, you can’t tell me you wouldn’t have to keep going. Some guys quit with a stipulation, like they’ll keep going if… I didn’t want to put myself in a situation where there was any stipulation.”

Now, the Todds run Limousin crosses, known for their feed efficiency and their lean meat, crossed with other breeds to produce more marbling, and they work with Wulf Feedlots in Nebraska and Wisconsin. Carly, who was once unsure of her unfamiliar role as a rancher’s wife, can’t imagine her life anywhere else.

“I really wasn’t so sure about all of it when we first got there,” Carly, who at the time had a newborn son, Colter Lee, and a 4-year-old daughter, Madilyn, said. “When we first moved, we didn’t have TV for a whole year. We finally did get a TV because the next December, I said I was calling Dish to get it because all of our friends were at the Finals. I got TV so I could watch all the people we knew.”

Colter is still close friends with his old rodeo buddies Cory, Cesar, and Derrick, who, even though they don’t quite have it in them to quit the rodeo lifestyle, look up to Todd and the decision he made for his family.

“I thought he’d quit rodeoing, but I didn’t think he’d quit roping,” 2017 World Champ Cory said. “I didn’t think he’d completely quit everything. He went to one amateur rodeo with me, and everybody was giving him heck. And that was the last one he went to. He wanted to make sure when he retired, he retired.”

Colter did make the one major exception to his no-nonsense retirement for Cory in 2010, when Cory knew months in advance that he didn’t have a partner for the 2010 BFI. He began harassing his rancher buddy for one more shot at the Feist.

“It took a lot of talking,” Petska said. “Because he told everybody he was retired. But at the end of the day, we were good enough friends and he knew I was in a bind and he helped me out.”

Carly entered Reno that year on a good horse they’d raised named Bowkay (the grey Derrick now rides at the longer-score rodeos and jackpots), and Colter decided he could help Cory and take a trip to support his wife.

“It was exactly how I remembered it,” Colter said. “If you’re confident and on a decent horse, you’d have a chance. We had a couple legs, and I made him rope them because of how I handled the steers. But I still could do it. I could get us back in the roping if I went at them. We didn’t win anything, but it was something.”

Since then, Colter’s been focused on his kids—Colter Lee, now 9, and Traven, 8, as well as his daughter Madilyn, 13. The Todds still raise great horses—Potter-ranch bred horses crossed on other stand-out studs like A Streak Of Fling and Blazin JetOlena. Madilyn, at just 11, qualified for the barrel racing in the American Semifinals in 2016. Colter Lee loves to rope with his dad in their arena at the house, where they keep anywhere between 10 and 30 heifers to rope at any given time. Colter Lee has even picked up broncs at local high school rodeos put on by their neighbors, the Resors of Salt River Rodeo. Traven found himself in love with bucking stock, so at just 8 he’s got some bulls from Owen Washburn.

“We rope for fun—it’s what we do. I don’t care if they catch or miss. We’re having a good time and that’s it. We’ll see what they want to do. I can’t say—if they want to, and it’s one of their dreams, I’ll be there.”

The kids have an idea about how great their dad was, but not because he tells them much about it.

“They know Derrick, and they know about the NFR a little bit,” Colter said. “They watch old tapes, but not like I did when I was a kid. They know Uncle Will (Woodfin, who is married to Savannah Todd) ropes, but they don’t follow it all year or anything.”

Colter’s kids might notice the Cheyenne buckle he wore until two years ago, when it got so thin with wear he took it off his belt, replacing it with a buckle he and Colter Lee won at a Labor Day family rodeo. He still wears his red Cheyenne finalist vest on cold mornings in Arizona, paired with a wild rag and chaps.

Todd might be more practiced-up with a King Ropes Ranch Rope than he is with the Fast Backs he used a decade ago, but there’s no doubt in his friends’ minds that he could be just as tough today as he was then with any sort of loop.

“He’d be back at the NFR this year if he wanted to,” Cory said. “He’s so talented. He’d have a good partner and be back with a chance to win the world. But for him, there’s not ever been that thought.”

“There’s not a story good enough you can tell about Colter,” Derrick added. “People say everyone is a good guy all the time, but when you share thoughts and cowboy stories and hanging out by the fire with someone, and you know what they want in life, you know what really makes up a good guy. Listening to a person pray, you find out a lot about somebody: how they think, how they live their life and work with an animal or live off the land. I think of him as one of my best friends, which I don’t have many of. But he’s kind of my hero, too. I always looked up to him and wanted to be like him. He’s one of the first guys I’d actually talk to about life other than roping. He was a friend outside the arena. Still, that’s who I talk to to this day. I talk to him more about life than anything else. He’s a Christian, a rancher, and a cowboy.”