For one person to start with an unruly 2-year-old and mold it into one of the best head or heel horses of all time takes an extraordinary bond, a lot of patience and, let’s face it, a little help from providence. The following five champions have trained—and continue to train—other great horses, but their favorite is always that project-turned-love-of-their-life that shaped their own legacy.

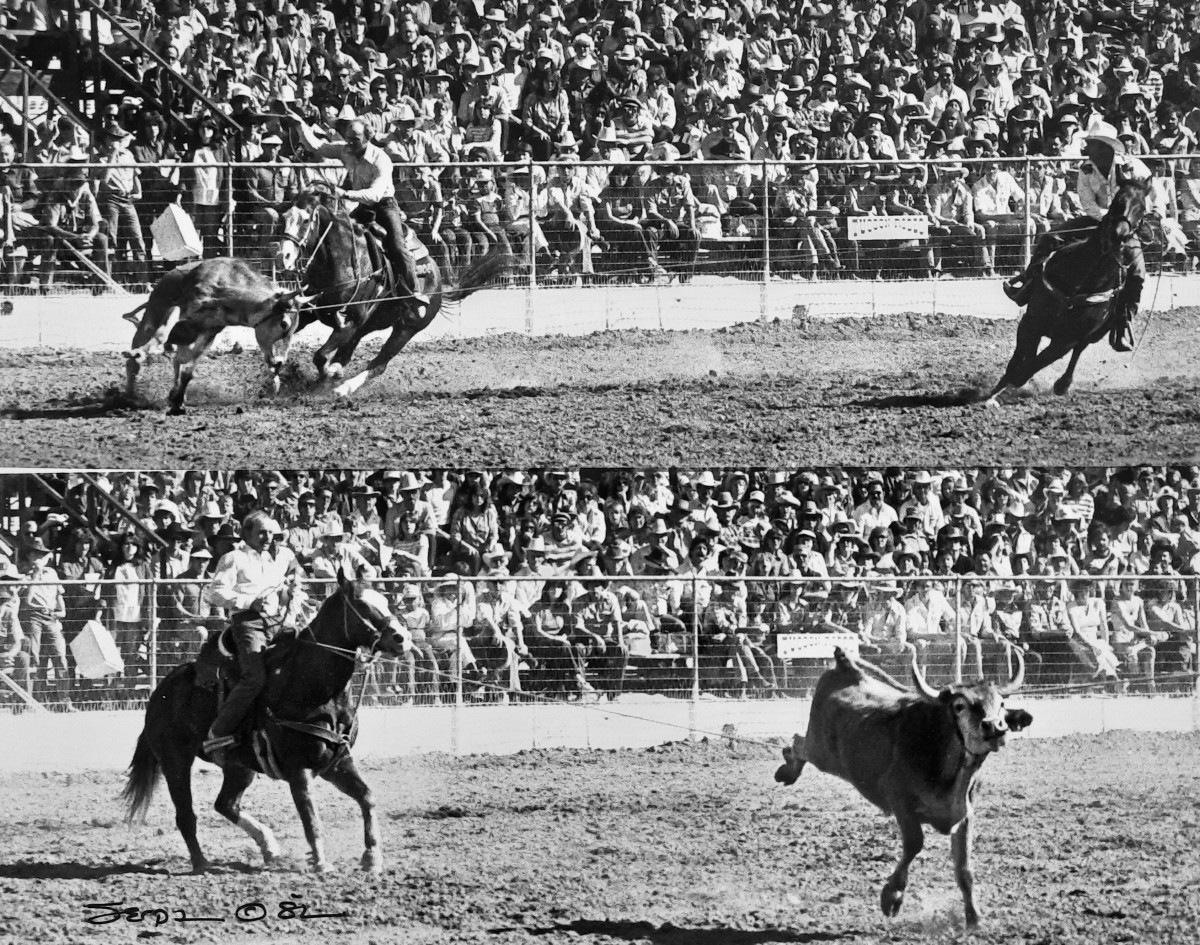

Louise Serpa Photos

Mo and Banner

Denny Watkins was winning the World at the ’78 NFR—until the 10th round.

“I lost the gold buckle on that last steer,” remembers Watkins, whom friends call “Mo” (from the nickname Denimo). “I rode back to my trailer, stepped off Banner and uncinched him. Took his bridle off and was just leaning against the door thinking, ‘I cannot believe it; I had it and I lost the world title.’ And that horse walked over to me and literally laid his head on my shoulder and just stayed like that. He could feel my pain. He was my best friend.”

Rewind to 1969. At 14, Watkins told his dad, Eddie, he wanted to start heeling. When some family friends produced a little bald-faced sorrel foal in ’69, the Watkins clan took notice. They’d heeled on the dam and headed on the sire. Eddie traded $300 worth of tin for the 2-year-old in ’71 and told his boy they’d learn to heel together.

Watkins jokes that he put Banner in draw-rings until he looked like he was ready to pull a wagon, because he knew nothing about breaking a colt. Countless miles out riding in fields cemented their bond. They chased lead steers as soon as the colt turned 3.

At 4, Banner helped his 18-year-old owner fill his permit and turn some heads with money up over a 35-foot score. Banner wasn’t heavy-made but was “unbelievably fast.” In June of 1974, NFR header David Motes asked the kid on the 5-year-old to rodeo. They won their first contest, the Reno Rodeo, and Watkins finished the season 16th.

He and Banner went on to win the NFR average twice (1981 and ’84), plus they won everything on dirty-big, hard runners over long scores and in mud and on grass (with no ice nails), and at Oakdale, Chowchilla and the BFI. Throughout, their bond just got tighter.

“We were both so young when we started, that horse was more like my dog,” Watkins said.

Banner also packed Watkins’ buddies to the pay window. At one NFR in the early 1980s, all 15 heelers had won at least one check on Banner that season.

“Clay Cooper, Al Bach, and the late Rickey Green rode him a lot and they loved him,” Watkins said. “Leo won second at Salinas on him one year. This was a phenomenal horse.”

Bob Ragsdale once placed at Roseburg on Banner—left-handed. In 1985, the horse won an AQHA Award of Merit for having been outstanding in his field for a full decade. But even back in ’75 at a roping in El Paso, Hollywood actor James Caan offered Watkins a blank check for him. Looking back, the 19-time NFR heeler figures his first heel horse taught him much more than he taught Banner.

“He was the best horse I ever had, and not because I trained him,” he recalled. “It was the will he had to win.”

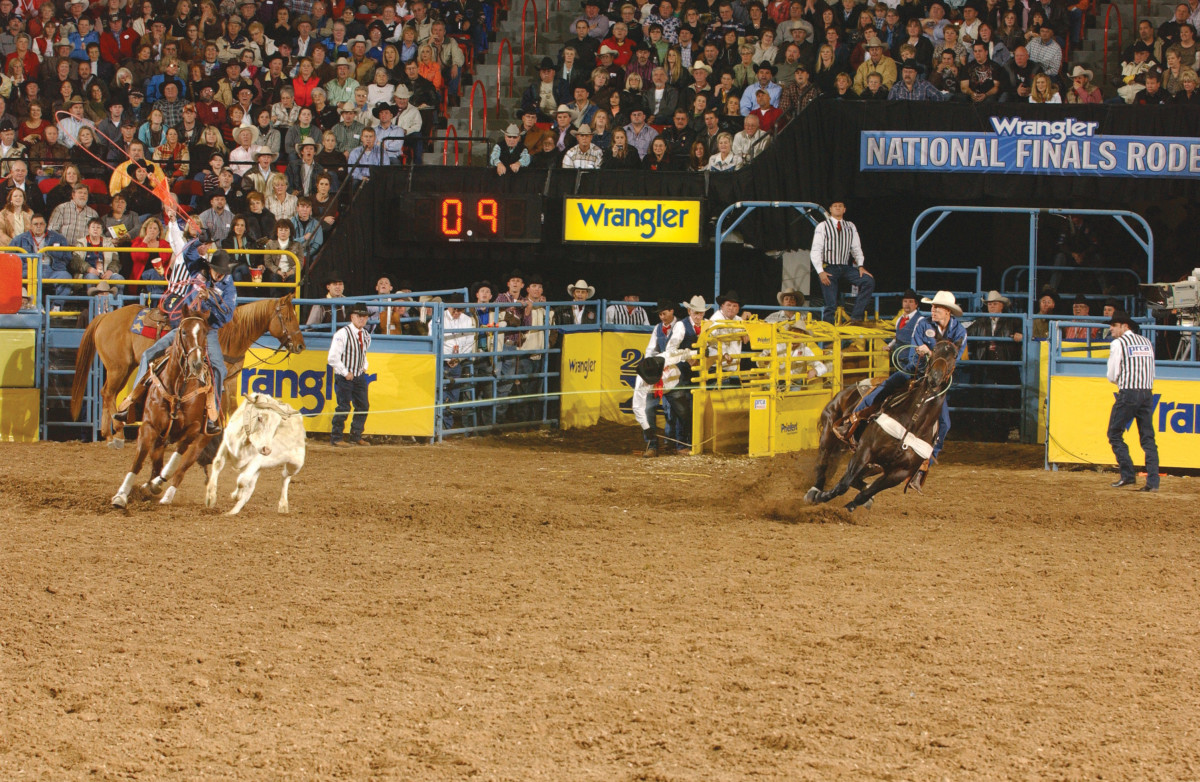

Hubbell Rodeo Photos

Travis and Edmond

When Joe Braman sent a sorrel weanling to the Woodard place in Stephenville, Texas, Travis had already finished and sold 2020 PRCA/AQHA Heel Horse of the Year “Sug” to Brady Minor and was busy breaking “Blueberry,” who has since packed Walt to wins in Fort Worth, Houston and Salinas.

Today, that sorrel weanling is 12. Registered as Mr JB 0834, “Edmond” is out of a Genuine Doc mare by JB’s stallion, Two Timen Fuel—half-brother to Charles Pogue’s great Scooter. Travis, an NFR heeler and BFI champ who quit rodeoing to raise kids and train horses, set the arena record at Pendleton on Edmond in the mud. In July, he and the horse bested 62 teams to win the Open World Series jackpot in Stephenville.

Truth is, he’d rather start a horse than buy one. Travis enjoys playing around and sacking out 2-year-olds so much that his goal is to eventually ride them with no bridle.

“My grandpa was a great horseman and I enjoy the little games I’ve learned to do with them to get flex and bend with a halter and longe line,” Travis said.

He line-drives all his colts with a nod to Sheldon Woodard’s teamster days, so “it’s not a Wild West show when I step on for the first time.” Travis likes to rope both ends on colts and even swims with them. A decade ago, when the summer days turned sticky, he’d go down to the pond at the end of his arena, jerk the saddle off, and hold Edmond’s tail while they swam every day.

“That kind of stuff makes them love you,” he said. “My grandpa used to say a guy needs to feed his own horse. If you’ve got help that puts the hay in the feeder and cleans the stalls, you’ll never have a real relationship with your horse like you would with a dog. You want to turn those barn lights on and have that horse nicker at you.”

Today, you almost have to pedal Edmond to get him to hit a walk. Travis tries to train that into his horses.

“Any idiot can make a horse run harder,” he said. “But can you make him use his speed efficiently? That’s the challenge.”

Today, Travis can beat the best in the world on Edmond, but the big sorrel shines as Wyatt Woodard’s head horse.

“He will lope alongside a steer with my 7-year-old boy, then I can saddle him the next day at the jackpot and win the Open with Driggers—having run no practice steers. I really love that horse for me and my family.”

James Fain Photo

John and Blue

“He’d rear out of the box and strike at his head, then run off on every steer,” John Miller recalled of the colt he helped start when he was 15.

Starting a colt from scratch is tricky enough. Now make it a former racehorse. In the late 1950s, a Thoroughbred colt that broke a shoulder racing was turned out on an Arizona ranch. Ben Johnson paid $600 for him. Miller, the Oscar winner’s nephew, was just a teenager living at Johnson’s California home to help Virgil Berry (World Champion Ace Berry’s dad) ride outside horses.

“When we got that colt, he was sound of body but surely not of mind,” Miller said with a chuckle.

He and Virgil developed a daily routine with ol’ “Blue.”

“We’d get up at daylight and make 10 laps on him every morning around that four-square-acre arena logging a 30-foot telephone pole,” Miller recalled. “Then, I’d run 15 muleys on him. I didn’t catch very many because he was running off. Then, Virgil would irrigate on him all day. Then I’d rope about 30 on him that night. We would score a lot of cattle, too. But I’d just as soon run one because it was safer with him running away with me than trying to flip over.”

Over time, it worked. Or, the way Miller puts it, one night they put him up and the next day he decided to be great. In 1960, Blue was only 6—and Ace 13 and John 18—when, against 167 teams at the pro rodeo in Salinas, the young permit-holders won the round.

“We won $1,100 on one steer,” Miller remembered. “That was a lot of money for an Okie kid. I was working for five bucks a day.”

Miller took Blue to college and went on to win two gold buckles, an NFR average title and the average at Salinas twice on the horse. Everybody rode him, from Jim Rodriguez Jr. to Sonny Cowden. And when Miller moved to Arizona, he put his heelers on him. How many horses have both headed and heeled at the NFR? Blue was that versatile, and was still good at 22.

“It wasn’t easy getting him broke,” Miller said. “He had a lot of steam to him. We didn’t fight him. You couldn’t. We just went at it until he decided he was a good one. When he was made, he was made. You could rope a 700-pound steer and jerk him straight over or puppy-dog him off. He was that good.”

Hubbell Rodeo photos

Dakota and Gina

She wasn’t yet 2, the tiny sorrel filly Dakota Kirchenschlager spotted in Texas in 2011. He was 19 and riding horses for Smokey Eppler.

“She was running up and down the fence and you’d swear she was going to run right into the fence,” recalled Kirchenschlager, now 29. “But she stopped really good at the corner and turned over herself and took off again. I watched her do that all day. It was amazing.”

He asked Eppler to price her. The old cowboy, never a fan of mares, did him one better and gave her to him.

“I thought, ‘Here’s your chance,’” said Kirchenschlager of his lifelong goal to train a horse he’d ride at the NFR. “I knew she could do it. There was just something about that horse; I just knew she was going to be the one.”

Nicknamed thanks to Martin Lawrence’s long, drawn-out “Damn, Gina!” from the 1990s TV show “Martin,” the filly was never registered. Kirchenschlager just backed in and started roping on her when she was barely 3.

“I definitely didn’t do things the right way,” he said. “But she was an amazing horse. She did anything you asked. Knowing what I do now, she was a freak of nature.”

When Gina was coming 4, Robbie Schroeder helped Kirchenschlager get her more broke. That made her super confident, and Kirchenschlager was tempted to take her rodeoing. He didn’t. In September, his header, Spencer Mitchell, told him, “If you’d have ridden that mare, we would have made the Finals.”

So that fall, he jumped on the filly that was turned out all summer. He entered—and won—her first amateur rodeo. The second rodeo of her life was Odessa, Texas—and Kirchenschlager won that, too, with Turtle Powell. She had no seasoning; Kirchenschlager would simply trot her for hours and get her tired when he was up. They won everything, including the first two rounds of the 2014 NFR. Kirchenschlager’s dream had come true. He took Gina back to the NFR two years later behind Tyler Wade and, in 2017, sold her to a family friend. Just this spring, Ross Ashford bought Gina and won $10,000 at the BFI with Dakota’s cousin Tate.

“The other day he had her at the USTRC Finals at Fort Worth,” Kirchenschlager said. “I walked up and that horse still remembered me.”

Hubbell Rodeo photos

Colter and Spice

In November 2007, Colter Todd’s wife, Carly, was videoing him practicing for his second NFR. He’d run 10 steers on 8-year-old Frisco—his buckskin Cheyenne and Pendleton champion—and 10 on 4-year-old “Spice,” a filly he had only been heading on for three months. After three days of watching, he couldn’t believe what he saw on video, much less felt.

“I started noticing this little mare really trying,” he recalled. “Giving me those good throws every day and those steers’ feet handling really good.”

She was in the trailer to Las Vegas soon, just for a grand-entry horse. But when Todd was almost to the Nevada line, he called his friend Rube Woolsey.

“I said, ‘What do you think about me riding this mare?’”

Woolsey suggested he try her on the first steer. So Todd demoted Frisco and snuck by Spice—who had only been to two amateur rodeos and jumped the barrier.

The rest is history. Todd and Cesar de la Cruz won two go-rounds and wound up third and second in the World, respectively. Spice took Todd back to Las Vegas in 2008, after setting arena records that season, and was then sold to Derrick Begay, who also picked up on her at PBR events.

“She tried hard forever,” Todd stated.

Spice was picked up as a grade filly from the Twisselmans’ Pick & Shovel Sale by Todd’s mother-in-law as a barrel prospect for Carly. Todd broke Spice and they ranched on her. But she didn’t love the barrels, and Todd needed a practice horse.

“She proved she had a lot of heart really fast,” Todd said. “She just kept scoring and running hard. I became a better trainer because of her.”

Todd prefers a green horse because they listen. That’s what made Spice so much fun for him.

“When she’d get insecure, instead of getting scared or frustrated, she’d just rely on me,” he recalls. “She’d do what I told her, whether it was score, run, duck harder, or pull up the fence.”

Todd got her to where she’d almost gain speed as she crossed the line inside the Thomas and Mack. Those are the little things he’s realized he can’t duplicate. But there’s always a chance—he has a yearling now out of Spice by Mel Potter’s late stud, Dinero.